News

Behind the Headlines

Two-Cents Worth

Video of the Week

News Blurbs

Articles

Testimony

Bible Questions

Internet

Articles (2012)

Internet Articles (2011)

Internet Articles (2010)

Internet Articles

(2009)

Internet Articles (2008)

Internet Articles (2007)

Internet Articles (2006)

Internet Articles (2005)

Internet Articles (2004)

Internet Articles (2003)

Internet Articles (2002)

Internet Articles (2001)

Montgomery,

Alabama targets 42 homes for

seizure through a "blight ordinance"

in a State that banned eminent domain.

A group

of Montgomery, Alabama residents—primarily minority citizens—are

fighting back against what they call Montgomery's "...reprehensible

practice" of seizing and demolishing homes in order to sidestep the

tough new eminent domain laws that were enacted after the US Supreme Court

ruled that cities could sue dwellings under eminent domain and sell the

land to commercial developers solely because the city would ultimately

profit from windfall taxes paid by Corporate America when they developed

the land for the overlords of commercial enterprise.  The

case that went to the Supreme Court? Kelo v City of New London

(545 US 469 [2005]). In 2001, a city-owned real estate development company,

New London Development Corporation seized six homes on 9-acres

adjoining 19-acres New London Development already owned in the

Fort Trumball area of New London. The 9-acre tract included the home owned

by Susette Kelo. The eminent domain seizure was done to help pharmaceutical

giant Pfizer, Inc. construct a 750 thousand square foot headquarters

for its research division on a 28-acre tract. Pfizer assured New

London the property seizures would add some 5,000 new jobs and some $12.5

million per year in local tax revenue to the city. Kelo and several

of her neighbors fought Pfizer and the City of New London, taking the

case to federal court. The residents lost the case when the Supreme Court

ruled, in 2005, that it was permissible to take private property and turn

it over to a commercial developer if it would economically benefit the

local economy.

The

case that went to the Supreme Court? Kelo v City of New London

(545 US 469 [2005]). In 2001, a city-owned real estate development company,

New London Development Corporation seized six homes on 9-acres

adjoining 19-acres New London Development already owned in the

Fort Trumball area of New London. The 9-acre tract included the home owned

by Susette Kelo. The eminent domain seizure was done to help pharmaceutical

giant Pfizer, Inc. construct a 750 thousand square foot headquarters

for its research division on a 28-acre tract. Pfizer assured New

London the property seizures would add some 5,000 new jobs and some $12.5

million per year in local tax revenue to the city. Kelo and several

of her neighbors fought Pfizer and the City of New London, taking the

case to federal court. The residents lost the case when the Supreme Court

ruled, in 2005, that it was permissible to take private property and turn

it over to a commercial developer if it would economically benefit the

local economy.  Forty-three

states, including Alabama, created State laws to protect private property

rights after the Kelo decision.

Forty-three

states, including Alabama, created State laws to protect private property

rights after the Kelo decision.

When she lost her court battle, Kelo sold the structure to preservationist Avner Gregory for $1 to keep it from being destroyed when Pfizer's new office complex was built. Gregory dismantled the structure and rebuilt it across town. Kelo, a nurse who still works in New London, moved to Groton after losing her home. (Last year Pfizer announced that it would close its Fort Trumball facility within two years. Pfizer has already laid off over 1,000 workers and expects to terminate the remaining workforce when it closes the complex and withdraws from New London.)

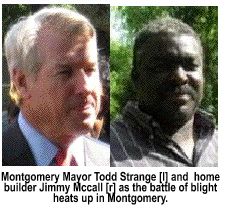

Because of the Kelo decision, Alabama enacted an eminent domain law that mandates eminent domain can only be exercised if the projects triggering eminent domain proceedings against homeowners are 100% publicly-financed for the good of the State, county or municipality. Thus, it appears the city of Montgomery may lack the legal authority to seize 29 homes since the local "blight ordinance" was passed, and to seize 13 more homes this year. Yet, without testing that authority before a State or federal judge, it continues to do so with impunity. When the Alabama Advisory Board found in favor of the homeowners of Montgomery against the city, it recommended that the US Civil Rights Commission investigate the city. When the US Civil Rights Commission ordered the city to appear and answer charges, no one from the City of Montgomery appeared.

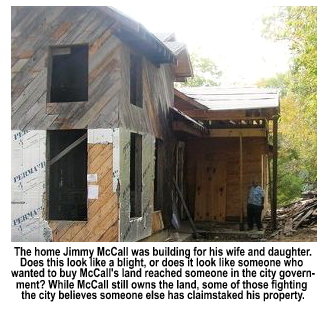

When the city tried to seize

Jimmy McCall's under-construction 5,000 square foot home in Montgomery

after several people approached him to sell them his land, McCall

took the City of Montgomery to court and won at both State and federal

level.  McCall

also secured an injunction that prevented any city official from setting

foot on his property.

McCall

also secured an injunction that prevented any city official from setting

foot on his property.

McCall was targeted by Montgomery's "blight law" because, he thinks, he chose to build his new home from salvaged and recycled lumber. Even though the City of Montgomery lost every court case, they declared McCall's still under-construction home a blight on the community, condemned it and demolished it—and billed him for the demolition. McCall's wife and daughter stood by crying as their dream was destroyed. (I don't know about you, but I've never seen a home construction site that was not a temporary blight. Apparently someone in the Montgomery City Council believes new homes cannot, or at least should not, be built from recycled lumber.

Interviewed by Fox News,

McCall said "...it was my dream house. The day they tore

it down my wife cried and my little girl cried. I never thought a municipality

or any other government agency would go against a court order. I never

thought they were that bold and arrogant and that they, you know, could

just say away with you—we're gonna do what we want to do, and they

did it. You know, they actually came out and did it."  McCall's

home was demolished in 2008. He has sued, won and had to appeal his victory.

In fact, it is on appeal now.

McCall's

home was demolished in 2008. He has sued, won and had to appeal his victory.

In fact, it is on appeal now.

Mayor Todd Strange told Fox News that he took office after McCall's under-construction home was condemned and demolished, which means he doesn't think his administration is liable for some other mayor's theft. Of course, it's his administration that's now using a blight ordinance to steal property not available to them under eminent domain. (Note: the demolition of McCall's under-construction home should legally obligate the city to condemn every new home under construction within the city, or it should obligate the city to replace what they destroyed. Not only McCall's unfinished home, but the homes of others like Karen Jones who told the Alabama Advisory Board that went she went out one afternoon she received a call from a neighbor that someone was demolishing her home. "When we got there," Jones told David Beito, chairman of the Alabama Advisory Board, "half the house—the back half of the house—was demolished. I said, let me see your paperwork. I need to know what you are doing here, because the taxes are paid on this land, and you're trespassing. And, they told me I couldn't be on the land while they were demolishing the house." Jones told Fox News that she had never been notified of a court hearing to determine the legal standing of the city to seize and destroy her generational family home.

"We have good evidence," Beito said, "that these homes are not in fact blighted, that is the pretext that they that they are blighted and that is why they are being demolished. Property owners are losing their land and I think that there is good reason to believe it often ends up in the hands of wealthy developers. It's eminent domain on steroids." Once again, for whatever it's worth, you have my two cents worth.

Copyright © 2009 Jon Christian Ryter.

All rights reserved.