News

Behind the Headlines

Two-Cents Worth

Video of the Week

News Blurbs

Articles

Testimony

Bible Questions

Internet Articles (2015)

Internet Articles (2014)

Internet

Articles (2013)

Internet Articles (2012)

Internet Articles (2011)

Internet Articles (2010)

Internet Articles

(2009)

Internet Articles (2008)

Internet Articles (2007)

Internet Articles (2006)

Internet Articles (2005)

Internet Articles (2004)

Internet Articles (2003)

Internet Articles (2002)

Internet Articles (2001)

n

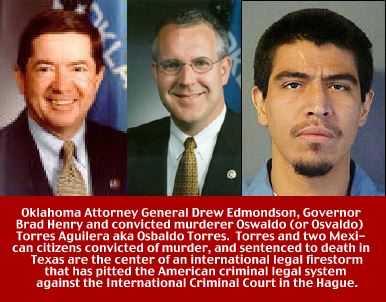

the early morning of July 12, 1993 Jorge Ochoa and Osvaldo Torres Aguilera,

aka Osbaldo Torres and Oswaldo Aguilera, broke into the Oklahoma City,

Oklahoma home of Francisco Morales and his wife, Maria Yanez. Torres

and Ochoa, who broke into the home to rob it, entered the Morales' bedroom

and reportedly awakened the sleeping couple. The intruders then opened

fire, killing Morales and Yanez in their bed. The shooting woke Maria's

14-year old daughter Christina who called 9-11 and reported that shots

had been fired. Only, according to the 9-11 tape, the 14-year old reported

that the shots may have been fired by her stepfather. Morales' 11-year

old son, Francisco also awoke when the first shot was fired. He witnessed

a man in a black T-shirt shoot and kill his father.

n

the early morning of July 12, 1993 Jorge Ochoa and Osvaldo Torres Aguilera,

aka Osbaldo Torres and Oswaldo Aguilera, broke into the Oklahoma City,

Oklahoma home of Francisco Morales and his wife, Maria Yanez. Torres

and Ochoa, who broke into the home to rob it, entered the Morales' bedroom

and reportedly awakened the sleeping couple. The intruders then opened

fire, killing Morales and Yanez in their bed. The shooting woke Maria's

14-year old daughter Christina who called 9-11 and reported that shots

had been fired. Only, according to the 9-11 tape, the 14-year old reported

that the shots may have been fired by her stepfather. Morales' 11-year

old son, Francisco also awoke when the first shot was fired. He witnessed

a man in a black T-shirt shoot and kill his father.

Christina testified that she peeked out of her bedroom and saw two men. One was wearing a white T-shirt. The other was wearing a black one. The man in the black T-shirt had something in his hand, but Christina admitted that she could not see what it was. After they were arrested a block or so from the Morales home by police responding to the "shots fired" call, Christina identified Ochoa as the man in the black T-shirt and Torres as the man in the white T-shirt. A few minutes before they broke into the Morales home, Ochoa and Torres parked their car at a friend's house. A witness at that location (identified from court transcripts as "Ms. Calderon") told police that one of the men --Torres--took a small handgun from the back trunk of the car and stuck it in his pants. (The description of the gun differed from the weapon which Ochoa used to commit the murders.) Police stopped the pair about a block from the Morales home because, as Oklahoma City police officers Coates and Mullenix testified at the trial, the men were nervous, sweating--and they had blood on their clothes. A search of the suspects produced sufficient evidence that they were the guilty party. Morales' billfold, containing $300 and the dead man's identification, and some of Maria Yanez's jewelry were found on Torres.

Positively identified by

Christina Yenez, Francisco Morales and Calderon, the pair was subsequently

tried in the District Court for Oklahoma County for the double murder.

The first trial was held in October, 1995. The trial judge was forced

to declare a mistrial when the jury could not reach a verdict Ochoa

and Torres were retried in February, 1996. Found guilty of two counts

of aggravated murder and one count of first

degree burglary in March of that year, both men were sentenced to death.

Ochoa appealed his conviction to the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals in 1998 arguing that when he was arrested he was not competent to stand trial; that his attorney was not competent; that he did not have an unbiased jury and that, for several reasons enumerated in the petition, he was denied due process.

On June 30, 1998 the Appeals Court ruled that Ochoa received a fair trial and the death sentence was upheld. Exhausting his own State post-conviction remedies, Torres filed a writ of habeas corpus pursuant to 28 USC ¤ 2254 asserting 26 violations of his constitutional rights. His petition demanded that Michael Mullin, the warden of the Oklahoma State Penitentiary release him from custody. His petition was denied.

Torres appealed to the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma. Once again, his petition was denied.

On January 23, 2003 Torres lawyers, Mark and Lanita Hendricksen of El Reno, Oklahoma appealed to the U.S. 10th Circuit Court of Appeals. After reviewing the case, the federal appeals court denied Torres's motion. The Hendricksens sought assistance from the Mexican government. At that time there were 52 Mexican citizens under death sentences for in eight States.

Mexican president Vincente Fox appealed to the Bush Administration which, of course, was powerless to intrude in State jurisdictional issues. In 2002 Texas governor Rick Perry (who was serving out the balance of George W. Bush's gubernatorial term) ignored appeals from Fox to spare the life of death row inmate Javier Suarez Medino. Medino was convicted of killing a Dallas undercover narcotics cop in 1989. Fox argued that because the Mexican consulate had not been notified when the Medino was arrested, he could not be executed. When Perry signed the execution order, Fox canceled a three day summit with President George Bush in Crawford to protest what he termed a violation of Medino's civil rights. (You may recall during the Clinton years that then Secretary of State Madeleine Albright tried to bully Virginia governor Jim Gilmore not to execute a Paraguayan national, Angel Francisco Breard arguing that it would put Americans at risk abroad. Gilmore ordered the execution of Breard to proceed after the Supreme Court failed to block the execution.)

In January, 2003, within days of losing their Circuit Court appeal, the Hendricksens filed another appeal on behalf of Torres, This time, a brief was filed in the U.S. Supreme Court. The Mexican government filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court noting that it had filed a lawsuit against the United States in the International Court of Justice--the World Court--in the Hague on that very matter. Mexico argued that the United States must abide by Article 36[1]b of the Vienna Convention by notifying Mexican authorities whenever they arrest a Mexican citizen. The State of Oklahoma did not notify Mexico that it had arrested Torres and charged him with murder. Nor did the State of Texas notify them when they arrested Cesar Robert Fierro Reyna and Roberto Moreno Ramos or 49 other Mexican nationals in eight States when they were arrested and charged with capital offenses. The U.S. Supreme Court, in a 7 to 2 decision, rejected Fox's argument out-of-hand and, thus rejected the Hendricksen Vienna Convention argument by refusing to hear the Torres case. Dissenting were Associate Justices John Paul Stevens and Stephen Breyer. Stevens, the most senior Associate Justice on the high court said in his dissenting opinion that notification is required by the Vienna Convention of which the United States was a signatory nation. Stevens added that since the foreign national in custody might not know he or she has the right to notify their consulate, Stevens felt the burden to do so should be placed squarely on the federal government. Breyer added in his dissent that the Torres case could have international implications. He suggested that by not abiding by the terms of the Vienna Convention the United States could easily affect America's relations not only with Mexico but other nations around the world. In addition, he said, it could also affect how Americans are treated overseas when they come into contact with law enforcement officials in those countries. "This case," he concluded, "raises important questions concerning the relation between, on the one hand, the domestic court in the United States and, on the other, decisions of the International Court of Justice interpreting the convention."

The U.S. Supreme Court in the Breard matter said that the Vienna Convention permits both State and federal courts in the United States to apply ordinary procedural and default rules barring defendants from raising a constitutional claim in federal court that he or she failed to raise in State court. "Given the international implications of the issues raised," Breyer concluded, "I believe further information, analysis and consideration are necessary. Depending on how the ICJ decides Mexico's related case against the United States, and subject to further briefings in light of that decision, I may well vote to grant [review] in this case. Consequently, I would defer consideration on this petition." Since Mexico had raised the question in the international legal arena, a copy of the Supreme Court's slap in the face of the World Court made its way to the Hague in the hands of Juan Manuel Gomez-Robledo and Santiago Onate as agents of the Mexican Ministry of Justice around the first of December.

Arguing the position of the United States for the Bush Administration was William Howard Taft IV. On December 15, 2003 the International Court of Justice (the World Court) heard the arguments in the case of Mexico v United Stales of America. The "trial" lasted four days, concluding on Friday, December 19. Interestingly, the decisions of the World Court are binding on all parties. There is no appeal since there is no higher court anywhere in the world. You might even say the International Court of Justice is now the "supreme" supreme court of the world. The Mexican government argued that United States violated the civil rights of 52 Mexican nationals who are now on death row in American prisons by not informing those arrested that they had the right to consular protection at the time of their arrest, causing Mexico to "suffer" by denying it the right to protect its nationals. Thus, Mexico demanded that the convictions of all 52 Mexican nationals on death row in U.S. prisons be overturned or, at least, that the U.S. government be obligated to hold clemency hearings for those nationals.

Taft, responding for the U.S. State and Justice Departments, argued that Mexico's demands "...are an unjustified, unwise and ultimately unacceptable intrusion into the United States criminal justice system." However, Taft's argument was problematic since the Nixon Administration signed the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations in 1969. One hundred sixty-four nations signed the protocol. In addition, Nixon's State Department signed a separate accord in which it agreed to submit to the jurisdiction of the World Court to interpret the Vienna Convention--and their right to settle all disputes that arose from it. In the past, the United States has invoked Article 36 whenever American citizens are detained in a foreign nation, All Article 36 does is require that arrested foreigners be told they have a right to speak with their consular officials--and that such requests by detainees be honored promptly. On December 23 the World Court ordered Texas and Oklahoma not to execute Torres, Reyna and Ramos--even though execution dates were not imminent in any of those cases-- until the 15 justices at the International Court of Justice had fully deliberated Mexico's request. A ruling by the World Court is expected sometime in February.

Copyright © 2009 Jon Christian Ryter.

All rights reserved.