News

Behind the Headlines

Two-Cents Worth

Video of the Week

News Blurbs

Articles

Testimony

Bible Questions

Internet Articles (2015)

Internet Articles (2014)

Internet

Articles (2013)

Internet Articles (2012)

Internet Articles (2011)

Internet Articles (2010)

Internet Articles

(2009)

Internet Articles (2008)

Internet Articles (2007)

Internet Articles (2006)

Internet Articles (2005)

Internet Articles (2004)

Internet Articles (2003)

Internet Articles (2002)

Internet Articles (2001)

![]() n

the 9-year legal battle over missing Blackfoot Indian royalties,

US District Court Judge Royce Lamberth has been a perennial

thorn in the side to the Justice and Interior Departments of both

Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. The case, filed

in Lamberth's court in 1996 is being fought over $137 billion

in missing oil, timber, and grazing royalties and other lease

payments due, not to the tribes but individually, to the Native

American members of what is generically referred to as the Six

Nations (now viewed as a composite of all of the known Indian

tribes) on over 54 million acres of land.

n

the 9-year legal battle over missing Blackfoot Indian royalties,

US District Court Judge Royce Lamberth has been a perennial

thorn in the side to the Justice and Interior Departments of both

Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. The case, filed

in Lamberth's court in 1996 is being fought over $137 billion

in missing oil, timber, and grazing royalties and other lease

payments due, not to the tribes but individually, to the Native

American members of what is generically referred to as the Six

Nations (now viewed as a composite of all of the known Indian

tribes) on over 54 million acres of land.

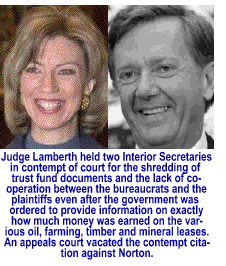

When

Lamberth—a colorful and very popular Washington, DC

US District Court judge—determined in a July ruling that

the failure of the Interior Department over several decades to

accurately account for billions of dollars owed to the Indian

tribes in the American Northwest was the epitome of incompetence

by apathetic bureaucrats whose job it was to accurately tally

the money owed to the Six Nations and to make timely and honest

royalty payments to those who owned the land and were legally

entitled to the proceeds from the royalties.

When

Lamberth—a colorful and very popular Washington, DC

US District Court judge—determined in a July ruling that

the failure of the Interior Department over several decades to

accurately account for billions of dollars owed to the Indian

tribes in the American Northwest was the epitome of incompetence

by apathetic bureaucrats whose job it was to accurately tally

the money owed to the Six Nations and to make timely and honest

royalty payments to those who owned the land and were legally

entitled to the proceeds from the royalties.

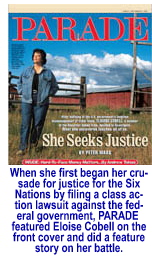

.jpg) The

lawsuit was originally filed in 1996 by a Blackfoot tribal leader,

Elouise Cobell, as Cobell v Babbitt when her action

was initially filed against the Clinton Interior Department

and its Secretary, Bruce Babbitt. Cobell, 59, a

Blackfoot banker from Montana filed the class action lawsuit based

on the terms of the Dawes Act of 1887. Under the Dawes

Act, the federal government initiated the practice of giving

land allocations to the individual Indians as their reservations

were reassumed by the government.

The

lawsuit was originally filed in 1996 by a Blackfoot tribal leader,

Elouise Cobell, as Cobell v Babbitt when her action

was initially filed against the Clinton Interior Department

and its Secretary, Bruce Babbitt. Cobell, 59, a

Blackfoot banker from Montana filed the class action lawsuit based

on the terms of the Dawes Act of 1887. Under the Dawes

Act, the federal government initiated the practice of giving

land allocations to the individual Indians as their reservations

were reassumed by the government.

Each reservation-dweller Native American family was given a tract. The balance of the former reservations were either retained by the government or sold to land developers, mining companies, or oil drillers and refiners after vast reservoirs of natural resources were discovered beneath the northern plains early in this century.

Today,

one Administration and a decade later, the 1996 lawsuit has been

amended as Cobell v Norton. Even under the "compassionate"

president, George W. Bush, the US government is not any

closer to reaching a settlement. Unfortunately, the "accounting"

of Indian wealth on-and-under the land given to the people of

the Six Nations by "Karanduawn," the "Great White

Father in Washington" has gotten worse. The government, according

to Deputy Interior Secretary J. Steven Griles, is clueless

how much—if any money—is owed to the Blackfoot and other

Indian tribes.  "Nobody

has shown me that there is a loss," Griles said.

"They haven't provided one shred of evidence [that the government

owes them anything]."

"Nobody

has shown me that there is a loss," Griles said.

"They haven't provided one shred of evidence [that the government

owes them anything]."

Let

me provide the Deputy Secretary with one example that at least

suggests maybe the Interior Department should use something other

than tongue-in-cheek invisible ink when they compute oil royalties

since the US government has been systematically cheating the Six

Nations since 1900 by paying royalties based on the price of oil

at the wellhead at the turn of the last century. .jpg) Eighty

year old Navajo grandmother Mary Johnson has four oil wells

on her farm that have been pumping oil steadily, around the clock,

for about 50 years. According to Johnson, the oil wells

have polluted all of the creeks running through her land. The

stench of crude fouls the air she breathes and has sickened her

livestock. Each month, just like clockwork, Johnson receives

a royalty check from the US Bureau of Indian Affairs. How much

is the check now that crude oil is selling for $68 per barrel?

The checks have never varied. They don't increase with rising

cost of crude. Johnson gets just about enough money to

fill her gas tank once a month—approximately $40. That's

the same amount she received in 1960 when the gasoline that now

sells for about $3 per gallon cost less than 20 cents a gallon—and

crude oil sold for less than $4 per barrel. According to attorney

Alan Balaran, who handled the case for Cobell for five

years until he recently resigned, citing government obstruction,

he uncovered evidence that the oil giants that own the leases

on the land were paying Native Americans significantly less than

they were paying non-Indian for the gas and oil rights on their

land.

Eighty

year old Navajo grandmother Mary Johnson has four oil wells

on her farm that have been pumping oil steadily, around the clock,

for about 50 years. According to Johnson, the oil wells

have polluted all of the creeks running through her land. The

stench of crude fouls the air she breathes and has sickened her

livestock. Each month, just like clockwork, Johnson receives

a royalty check from the US Bureau of Indian Affairs. How much

is the check now that crude oil is selling for $68 per barrel?

The checks have never varied. They don't increase with rising

cost of crude. Johnson gets just about enough money to

fill her gas tank once a month—approximately $40. That's

the same amount she received in 1960 when the gasoline that now

sells for about $3 per gallon cost less than 20 cents a gallon—and

crude oil sold for less than $4 per barrel. According to attorney

Alan Balaran, who handled the case for Cobell for five

years until he recently resigned, citing government obstruction,

he uncovered evidence that the oil giants that own the leases

on the land were paying Native Americans significantly less than

they were paying non-Indian for the gas and oil rights on their

land.

Griles insists there is no evidence that the government owes the 50,000 member Blackfoot tribe—or any other tribe—money. He insisted it is incumbent upon the plaintiffs to prove the allegations that they've been cheated by the federal government. Several independent investigations have found enough evidence to convince Lamberth the action filed by Cobell has merit. Cobell's lawsuit was certified as a class action.

(She also represents close to a half million Cree, Navajo, Cherokee, Piute, Apache, Sioux, Mohawk, Seneca, Iroquois, Seminole, Tuscaroras, Cayagas, Oneidas, Ojibway, Onondagas, Shoshoon, and another dozen or so lesser known Native American tribes seeking $137 billion in damages for "missing" Indian Trust royalties.)

Even though the government initially insisted that its Indian Trust records were up-to-date and in good shape, a review ordered by Lamberth supported Cobell's contention that the Interior Department never kept complete records of lease payments by the oil companies, loggers, and agri-giants that leased vast tracts of farmland. In addition, Lamberth's investigation revealed that unknown amounts of Indian Trust money was simply deposited in the general treasury to help balance the federal budget. And, Lamberth learned, both the Clinton and Bush Administrations let oil and gas companies exploit Indian lands at bargain basement rates for what could be nothing other than quid pro quos.

Judge

Lamberth described the case as the "...gold standard

for mismanagement by the federal government for more than a century."

In

1999 Lamberth ruled that the government had breached its

fiduciary responsibilities to the trust. In the last hearing,

in August, 2005, Lamberth chastised the federal government

when he said: "On numerous occasions over the last nine

years the Court has wanted to simply wash its hands of Interior

and its iniquities once and for all. But doing so," he

concluded, "would constitute an announcement that negligence

and incompetence in government are beyond judicial remedy."

In point of fact, Lamberth's worst fears have become

fact. Our Constitution, and the liberty we have historically construed

as God-breathed and inherent, is now construed by the government

to be conditional—and based not on the Constitution of the

United States but the UN Declaration of Human Rights whose privileges

of liberty are retractable gratuities.

In

1999 Lamberth ruled that the government had breached its

fiduciary responsibilities to the trust. In the last hearing,

in August, 2005, Lamberth chastised the federal government

when he said: "On numerous occasions over the last nine

years the Court has wanted to simply wash its hands of Interior

and its iniquities once and for all. But doing so," he

concluded, "would constitute an announcement that negligence

and incompetence in government are beyond judicial remedy."

In point of fact, Lamberth's worst fears have become

fact. Our Constitution, and the liberty we have historically construed

as God-breathed and inherent, is now construed by the government

to be conditional—and based not on the Constitution of the

United States but the UN Declaration of Human Rights whose privileges

of liberty are retractable gratuities.

Lamberth ruled in July that the Interior Department's failure over several decades to account for billions of dollars due to Native Americans by the Bureau of Indian Affairs constituted "...outright evil, apathy, cowardice or crushing bureaucratic incompetence..." Lamberth told one Interior Department witness: "You know any banker would be in jail for handling funds like this, don't you?" The government lawyers, who feared the stinging wrath of the judge, cringed and decided that Lamberth had to go if they were ever going to prevail.

On August 15 the Justice Department filed a brief with the US Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia requesting that Lamberth be removed because he not only used intemperate language towards the government's lawyers, he ignored appellate rulings and accused the government of "...falsification, spite and obstinate litigiousness [with] no legal or factual basis." There was nothing wrong or improper in Lamberth's accusations towards the government's lawyers—particularly since Lamberth was correct. The Justice Department knew that not only was the US government was about to lose the biggest lawsuit in American history, the bureaucrats at the Department of Indian Affairs were going to be branded as thieves of the worst sort—stealing not from the richest, but the poorest, of all Americans.

The appellate court is actually considering the government's request. Clearly, if the Circuit Court of Appeals grants the government's wish, it will erase Cobell's chances of winning her lawsuit since the Justice Department will hand-pick a federal magistrate who will be much more sympathetic to the government's position.

Cobell has devoted most of her life to this issue. She travels between Washington and her home near Glacier National Park in Montana 40 weeks a year. Cobell admits she is not absolutely certain of the total amount owed to Native Americans, but only because she isn't certain precisely how much land the 300 to 500 thousand plaintiffs in her action actually own.

The

Bush Administration—like the Clinton Administration

before it—tried unsuccessfully to remove Lamberth

from the case, hoping another judge would dismiss the lawsuit.

Sen. John McCain [R-AZ] who chairs the Senate Indian

Affairs Committee decided the only way this case will ever

be resolved is to legislate a solution. In the spring of 2004

McCain asked Cobell what reforms in the Bureau

of Indian Affairs she felt were needed, and what realistic

amount would have to be offered for Cobell to settle the

lawsuit. Cobell responded with 50 items that needed to

be included in McCain's legislation to solve the problems

in the Bureau of Indian Affairs, In addition, she said

the Six Nations would settle for a cash payment of $27.5 billion—that

was exempted from any taxes. The amount, she argued, was far less

than the government actually owed the Indian Nations.

The

Bush Administration—like the Clinton Administration

before it—tried unsuccessfully to remove Lamberth

from the case, hoping another judge would dismiss the lawsuit.

Sen. John McCain [R-AZ] who chairs the Senate Indian

Affairs Committee decided the only way this case will ever

be resolved is to legislate a solution. In the spring of 2004

McCain asked Cobell what reforms in the Bureau

of Indian Affairs she felt were needed, and what realistic

amount would have to be offered for Cobell to settle the

lawsuit. Cobell responded with 50 items that needed to

be included in McCain's legislation to solve the problems

in the Bureau of Indian Affairs, In addition, she said

the Six Nations would settle for a cash payment of $27.5 billion—that

was exempted from any taxes. The amount, she argued, was far less

than the government actually owed the Indian Nations.

Cobell

told McCain that Congress would have to appropriate new

funds (not money from the Indian Tribe funds) to settle the claim

since she knew if the "source" of the payment was not

specified in the legislation, the government would simply shift

funds from some other Indian relief program.  Cobell

also asked that a new Deputy Secretary of the Interior be appointed—a

Native American—who would have complete oversight of the

agencies that manage the Indian Trust.

Cobell

also asked that a new Deputy Secretary of the Interior be appointed—a

Native American—who would have complete oversight of the

agencies that manage the Indian Trust.

McCain balked at all of her recommendations. The $27.5 billion, he said, was "...just way out of sight," adding that Congress would not appropriate "new money" to settle an old debt. The legislation, he said, would be the place where negotiations began. McCain introduced a bill which he called "...a starting point," knowing if the bill was passed and signed into law, it would become the final resting place of the Indian Trust claims. The bill does not mention any dollar amount that was construed to be "owed" to the Six Nations.

The plaintiffs in Cobell v Norton reacted angrily when they realized that the Chairman of the Indian Affairs Committee was not interested in resolving the lawsuit, only ending it. Cobell, in an interview with the Rapid City, SD Journal compared the McCain bill to the infamous Baker Massacre (considered to be the worst slaughter of unarmed American Indians by US troops). The comparison to the Baker Massacre brought the famous McCain temper to a boil as he defended his legislation in an Indian Affairs Committee meeting where he said the bill "...reflects extensive listening to the parties in the litigation, and it cannot credibly be compared to a massacre even in a figure of speech." McCain then advised the plaintiffs in Cobell v Norton to grab the chance to sit down with lawmakers and negotiate. "Leave the rhetoric to others," he advised Cobell. "You won't have this opportunity again anytime soon." (My observations of "government in action" is that anytime American citizens are willing to surrender their rights, government always has an outstretched hand.)

McCain's legislation would provide for a lump sum payment of whatever amount was deemed by the "appropriate authority" to be owed to the plaintiffs through a settlement fund administered by the US Treasury. One basic remains unanswered. How much money has the US government earned from leasing Indian land? No one knows. But it is likely in the hundreds of billions over the last 118 years.

Ultimately what happened was the appointment of two mediators— approved by both sides—to attempt to iron out differences and arrive at a compromise that will work for both parties.

I guess it can honestly be said that the most heavily taxes Americans are Native Americans. It can also honestly be said that the American Indian has been taxed into poverty. You might also say that Sen. John McCain was Gen. George Custer's revenge on the Six Nations for the Little Big Horn.

Copyright © 2009 Jon Christian Ryter.

All rights reserved.