News

Behind the Headlines

Two-Cents Worth

Video of the Week

News Blurbs

Articles

Testimony

Bible Questions

Internet Articles (2015)

Internet Articles (2014)

Internet

Articles (2013)

Internet Articles (2012)

Internet Articles (2011)

Internet Articles (2010)

Internet Articles

(2009)

Internet Articles (2008)

Internet Articles (2007)

Internet Articles (2006)

Internet Articles (2005)

Internet Articles (2004)

Internet Articles (2003)

Internet Articles (2002)

Internet Articles (2001)

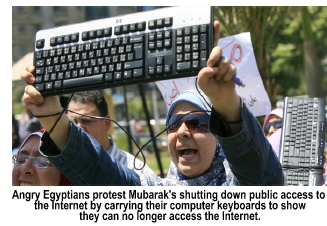

![]() mboldened

by what the media purported to be a "people's revolution" that

toppled the regime of Tunisian strongman Ben Ali over, the media

reported, rising unemployment and Ben Ali's corruption, the "freedom

movement" instigated by the Muslim Brotherhood leapfrogged

Libya and brought its Islamic brand of political unrest to Egypt. Egyptian

strongman and President Hosni Mubarak was ready. Among the first

things he did, at 10:12 p.m. on Thursday, Jan. 27, 2011 was to tell his

minions to instruct Telecom Egypt to shutdown both the Internet

and cell phone service.

mboldened

by what the media purported to be a "people's revolution" that

toppled the regime of Tunisian strongman Ben Ali over, the media

reported, rising unemployment and Ben Ali's corruption, the "freedom

movement" instigated by the Muslim Brotherhood leapfrogged

Libya and brought its Islamic brand of political unrest to Egypt. Egyptian

strongman and President Hosni Mubarak was ready. Among the first

things he did, at 10:12 p.m. on Thursday, Jan. 27, 2011 was to tell his

minions to instruct Telecom Egypt to shutdown both the Internet

and cell phone service.  At

about 12:20 a.m. on Friday, Telecom Egypt went offline. Fourteen

minutes later, the other four Internet and cell phone providers went dark.

While this was the first national attempt to close all of the onramps

to the Information Superhighway over a long period of time, it was actually

the third attempt by a government to exercise what every government in

the world possesses—a kill switch to shut off the Internet

and interrupt its journey through cyberspace. The protesters in Egypt—both

domestic and foreign—used the Internet to share information among

one another and organize demonstrations. Social networking sites like

Facebook and Twitter were the primary communications vehicles to organize

against the government.

At

about 12:20 a.m. on Friday, Telecom Egypt went offline. Fourteen

minutes later, the other four Internet and cell phone providers went dark.

While this was the first national attempt to close all of the onramps

to the Information Superhighway over a long period of time, it was actually

the third attempt by a government to exercise what every government in

the world possesses—a kill switch to shut off the Internet

and interrupt its journey through cyberspace. The protesters in Egypt—both

domestic and foreign—used the Internet to share information among

one another and organize demonstrations. Social networking sites like

Facebook and Twitter were the primary communications vehicles to organize

against the government.

The first country to test its kill switch was China. On June 3, 2009, one day before the 20th Anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre in Beijing, the Chinese government shut down the ability of their citizens to access the Internet. In addition, during the downtime, international sites like Blogger, Flickr, Facebook, Twitter, Wordpress and Hotmail were placed behind the Great Firewall of China.

The second country to test

its kill switch was Australia on Sept. 2, 2009. But, before that,

on March 18, 2009, Wikileaks published a list of 2,300 Aussie websites

which the Australian Labor Party put on its political "hit list."

The social progressive globalists in the land down under do not like conservatives

and view them as a threat to their agenda.

They were already making plans to shut down a couple thousand problematic

websites, which would be camouflaged by an assortment of porn and network

marketing sites also targeted for extinction. Several of the targeted

conservative sites were anti-abortion websites. Most of the other targeted

sites were purely political. Several dealt with exposing government attempts

to stifle speech through filtration devises that censor content over the

world wide web. As the government answered the Wikileaks accusations,

they admitted they had blocked some political content but insisted they

did so only because they originated in other countries and were "piped

into Australia" to inflame the citizens.

Exercising the kill switch in Aussieland was easier than it was in Egypt only because all of Australia's Internet service providers get their cyberspace access through State-owned Telstra. On Sept. 3, 2009 the Sydney Morning Herald reported that for one hour, from 7:50 to 8:50 a.m., Telstra's international Internet network went down. A Telstra executive, Craig Middleton, told Skye News that customers could not access any international or Australian websites. Since roughly 95% of all Internet users used Telstra, almost every home and business in the nation and every cell phone user in the country was affected. What Australia was checking was whether or not they could shut down the Internet to private consumers but keep it open for use by the government—and a select group of industrials and businessmen. They found they could.

Middleton's explanation would have the Australian people—and those following the story worldwide—believe that the shutdown was a fluke caused by Aussie websites on ISPs tied to Telstra using links tied to websites in the United States, Canada, England or elsewhere in the world, suggesting that the international connections caused some sort of cyber-meltdown. It would have been easier for Middleton to tell the truth and admit that the government was testing its kill switch. Of course, an honest answer to the question would have ended Labor Party Prime Minister Kevin Rudd's career. But then, it still did. While the Labor Party held the government in the June, 2010 election, Rudd was replaced by current Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard. After the Rudd government shut down the Internet, Rudd's popularity dropped to 21%. It amazes me how the voting public continues to elect to office social progressives throughout the world when the core objective of communists (which they are) is to subjugate the people under their political control, under the pretext of taking the wealth of the rich and giving it to the poor. (In reality, the wealth the social progressive steals is the sweat equity wealth of the middle class which controls the majority of the votes in any democratic society. By reducing the middle class to the underclass, the classless society then becomes the chattel of the social progressive elites who become the masters of the universe.) Controlling free speech is a necessary step in achieving that objective.

In

April, 2009, Sen. Jay Rockefeller [D-WV] introduced the first

kill switch piece of legislation—The Cybersecurity Act of

2009—in the US Senate. Details about the legislation were posted

on this website on Aug. 23, 2009. Rockefeller's bill scared the

members of both the House and Senate that it went nowhere—even though

the far left had a death grip on both Houses of Congress. But, in this

instance, every Democrat in both Houses knew if they voted for the bill,

their political careers would be over. It could not get out of committee.

In

April, 2009, Sen. Jay Rockefeller [D-WV] introduced the first

kill switch piece of legislation—The Cybersecurity Act of

2009—in the US Senate. Details about the legislation were posted

on this website on Aug. 23, 2009. Rockefeller's bill scared the

members of both the House and Senate that it went nowhere—even though

the far left had a death grip on both Houses of Congress. But, in this

instance, every Democrat in both Houses knew if they voted for the bill,

their political careers would be over. It could not get out of committee.

On June 10, 2010, Senators Joe Lieberman [I-CT], Susan Collins [R-ME] and Tom Carper [D-DE] (all Northeast US liberals) introduced the Protecting Cyberspace as a National Asset Act. Seven days later the Huffington Post revealed that Lieberman's bill, like Rockefeller's before it, contained a provision that gave Barack Obama the right to use the kill switch and shut down the Internet if he felt there was a cybercrisis severe enough to merit it. The bill, according to the Huffington Post, would require that private ISPs, search engines and even software companies, immediately comply with any emergency measure mandated by the Department of Homeland Security or face fines, sanctions or loss of license.

In Obama's case, the Election of 2010 was a severe enough crisis since the Tea Party, which received no mainstream media coverage, effectively used the Internet to upset scores of races, took over the House of Representatives and put themselves back in the ball game in the Senate. Barack Obama cannot afford conservatives to have this type of unbridled access to the Internet in 2012 since it will allow the right to mobilize against the Soros-tactics of the far left.

Add to that a new bill introduced in the House of Representatives on March 15, 2011 by Congressman Jim Langevin [D-RI] that would give the Dept. of Homeland Security authority to decide which—and when—private ISPs can be regulated as "critical infrastructure." His bill, HR 1136, the Executive Cyberspace Coordination Act (which will amend Chapter 35 of Title 44 [remember this reference—it will be very important in a couple of minutes] to create a National Office for Cyberspace that will fill in some of the bureaucratic holes deliberately left in Lieberman's 221 page Cybersecurity and Internet Freedom Act of 2011 that replaces last year's Protecting Cyberspace as a National Asset Act. Co-sponsoring the legislation were Robert Andrews [D-NJ], Roscoe Bartlett [R-MS], Norman Dicks [D-WA]. Dutch Ruppesberger [D-MD], and Loretta Sanchez [D-CA]. (Note: it is very important for the American people to understand that none of the nations who created laws to allow their governments to shut down the Internet enacted those laws to protect their nations from cyberterrorists. Even though every government in the world mistrusts its allies as much as its enemies, and fears a catastrophic cyberattack, they fear their citizens far more.)

Lieberman's Protecting Cyberspace as a National Asset Act of 2010 did not fare any better than Rockefeller's Cybersecurity Act of 2009. Laws that abrogate the constitutional rights of US citizens don't sit well with the voters. That's why the framers of negative bills bury those negatives in previously enacted laws, or by creating other new bills which serve as parking lots for the negative clauses they do not want to appear in bills they know will be closely scrutinized and which, by themselves, don't make much sense to those who stumble across them.

Last fall, when Obama

realized that Lieberman's bill was not going anywhere, he decided

to enact the legislation by Executive Order, and instructed the Federal

Communications Commission [FCC] to assume regulatory control of the

Internet and implement Lieberman's still-buried-in-committee bill.  Gary

Kreep, former Executive Director of United States Justice Foundation, now a federal judge, uncovered the scheme in December, 2010, shortly before the FCC was scheduled

to vote on the matter. Even though, in a 3-to-2 vote, the FCC ruled they

had the authority to regulate the Internet, the 112th Congress had a different

view. Kreep used the Internet to warn Americans what the FCC takeover

of the Internet meant, and that there was a kill switch in the new regulations

that would allow Obama to shut down the Internet in the event of

any number of self-described cybercrises.

Gary

Kreep, former Executive Director of United States Justice Foundation, now a federal judge, uncovered the scheme in December, 2010, shortly before the FCC was scheduled

to vote on the matter. Even though, in a 3-to-2 vote, the FCC ruled they

had the authority to regulate the Internet, the 112th Congress had a different

view. Kreep used the Internet to warn Americans what the FCC takeover

of the Internet meant, and that there was a kill switch in the new regulations

that would allow Obama to shut down the Internet in the event of

any number of self-described cybercrises.

Kreep's advocacy in December triggered a scramble on the part of the far left to create a new bill that would disarm the American people enough to propel the legislation to Obama's desk for his signature. For that reason, the newest attempt to fool the people is called the Cybersecurity and Internet Freedom Act of 2011. The preamble of the bill is deliberately designed to deceive the American people into believing that "...the Government must not encroach on rights guaranteed by the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States...." by making it fuzzily clear, in line 10 of the preamble, that "...neither the President, the Director of the National Center for Cybersecurity and Communications, nor any other officer or employee of the Federal Government should have the authority to shut down the Internet" (Note: subsection 10 of the bill's preamble [lines 18 to 22] does not specifically deny anyone the right to shut down the Internet, it merely suggests they shouldn't—not that they can't. Left open is a collective consensus—a "consortium decision" rather than an individual decision to shut down the Internet for the good of the nation. Lines 18 to 22 would have us believe that one person alone might attempt to abrogate our rights, but that a consortium of bureaucrats working for that same wanabee dictator would somehow not allow the despot to shut down the Internet unless it was absolutely and unequivocally necessary to protect the security of the United States.)

Skipping the master touch of the disarming preamble of the Cybersecurity and Internet Freedom Act, let's move to the subtle surprises within the legislation where the politicians use their bureaucratic sleight-of-hand to take away from you everything the name of legislation promises to grant. It is purely smoke and mirrors since the actual regulations that grant, or restrict, your Internet freedoms do not appear in this bill. They are referenced in the bill, but many of those cited regulations do not yet exist since the the verbiage that creates them are parts of other pieces of pending legislation that do not yet exist, thus we have no inkling of just what rights we will possess when this piece of legislation is enacted unless the peripheral pieces of legislations, or amendments to existing legislation which are supposed to safeguard our Internet access, and use, are spelled out and enacted first.

On page 70, the bill provides a few hints of the rights of the citizens will enjoy under the Cybersecurity and Internet Freedom Act. I say "hint" because the promises made in the text are dependent on the legislation cited being enacted. But we know—because the bill says so—specifically Section 242(e) which converts the FCC into the National Center for Cybersecurity and Communications and also creates the position of "Privacy Officer" who will be among those who writes the as yet not written rules to theoretically protect the rights of the citizens.

As is usually the case with Congress, they write skeletal laws that leave everything to the imagination because the verbiage which backs up the rhetorical promises is conspicuously absent. The "cyber-rights" of the American people which appear as references to other sections of this bill, or other pieces of new or existing legislation, won't be written by the Director of Cyberspace Security—with the consultation of the US Attorney General, the Director of National Intelligence and the Privacy Officer—or amended, until after the legislation is signed into law. And, of course, by that time, when you discover that the "people's rights" promised by political rhetoric are virtually nonexistent or conditioned on "good behavior," it's too late. We need to force Congress to post every bill online for pubic scrutiny before those bills come up for an "aye" or "nay" vote. And, if every "i" is not dotted and every "t" is not crossed, and every word not spelled out, and every wart and pimple fully disclosed within the text and not by reference to some obscure, nondescript clause in some old law that is being amended, or some as yet not enacted piece of legislation.

Here is the simple reality of the Internet. Today you have an unbridled, constitutional right to use to the Internet without any regulations based on the 1st Amendment prohibition of anyone amending that right. Although that right has been affirmed three times in the federal courts, Obama believes he has executive authority, without legislative action by Congress, to arbitrarily overrule the federal judiciary by Executive Order—an Executive Branch interoffice memo that has absolutely no legal standing as law.

On June 22, 2004, in American Civil Liberties Union v Reno, a three judge Third Circuit Court panel ruled that the Internet is a "...publishing medium [in which]...personal home pages are the equivalent of individualized newsletters about that person or organization..." (929 F. Supp at 837).

The judges, and the US Supreme Court concluded that the Internet deserves at least as much protection under the 1st Amendment as printed matter receives. The Third Circuit emphasized that any analysis of the 1st Amendment protections afforded to a particular mass media communications must focus on the underlying technology that brings the information to the end user. Thus, they concluded, the Supreme Court's two primary theories for government regulation of any form of broadcast communications content—NBC v United States (319 US 190 [1943]) and FCC v Pacific Foundation (438 US 726 [1978]) do not justify government regulation of the Internet.

In American Civil Liberties Union v Reno, the Third Circuit very carefully delineated that the web carries the same fundamental First Amendment rights enjoyed by print newspapers even though the website seeking protection may be a kitchen table, laptop computer project and not a cold, impersonal monolithic media corporation with nine-digit capitalization and a staff of a 100 nameless reporters.

The real tragedy of the Cybersecurity and Internet Freedom Act of 2011 is that if the American people—using the Internet—do not get the word out fast enough, and far enough, the odds are better than 80% that this legislation will become law solely because of the political stroke of genius of including, in the preamble, what will appear to the reader to be a prohibition on the part of government to shut down the Internet

The legislation vaguely claims it will protect the right of private citizens to use the Internet without filling in the blanks by explaining what those rights are. Or for that matter, precisely which citizens it will protect. On the flip side, it gives the government a vaguely-defined right to define vaguely-described situations as "cybercrises" that will permit government to declare a national emergency that will then allow a grant of extraordinary authority. I say this not because I saw it in the Cybersecurity and Internet Freedom Act. I didn't.

The verbiage of the bill is a jigsaw puzzle of unanswered references to other pieces of legislation, written and/or still pending. When Congress enacted Obamacare, one part of it—Obama's Death Board—was enacted a year before Obamacare in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Franklin D. Roosevelt's right to create fiat money was not found in the Emergency Banking Relief Act of 1933 nor in the Gold Reserve Act of 1934 which was enacted on Jan. 30, 1934—a day before Roosevelt used Presidential Proclamation 2072 to devalue the dollar by reducing the value of the gold by 41%.

The authority to do so was buried in Title 3 of the Agriculture Adjustment Act of 1933. A farm bill. When he issued Presidential Proclamation 2078, FDR cited his authority as Title 3 of the Thomas Amendment of May 12, 1933. You might think the references you find in the Cybersecurity and Internet Freedom Act of 2011 to Chapter 35 of Title 44 will direct you to a law dealing with either the Internet or the FCC or, at least, newspaper publishing or free speech issues. Title 44 of the US Code deals with the production and procurement of congressional printing and binding. Chapter 35 deals with the coordination of federal information policy as it applies to records management of reports and documents. This is where the Obama Administration plans to park the regulations dealing with the management of the as yet undefined Department of Infrastructure Protection and the Office of Cybersecurity Protection. it would seem, since this new entity appears to be part of the Homeland Security, you would tie it to legislation which created that government body, particularly since the bill itself purports to "...amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002." Or just as appropriately, to amend it to the Communications Act of 1933 since that is the law which gave life to the FCC.

That question aside, here is another one that begs an answer. Why has the Obama Administration tried three times in two years to enact legislation to regulate how its citizens use the Internet? According to the legislation itself, it claims that "...cyber attacks are a real and evolving threat to the information infrastructure and economy of the Nation, the Sergeant at Arms of the Senate reported in March, 2010 that the computer systems of Executive Branch agencies of the Federal Government and Congress are probed or attacked an average of 1,800,000,000 times per month..." (What is really being said here is that citizen visits to government websites appears to approach some two billion hits a month. Equating them to terrorist attacks, spam attacks or serious attempts to hack into government databases which likely occur several thousand times a month is fanciful at best—which, likely, is why the authorship source was attributed to the Sergeant at Arms of the Senate, who is simply the Senate doorkeeper and a glorified usher with the power to eject troublesome spectators from the gallery of the Senate.) The Senate Sergeant at Arms, like the House Sergeant at Arms is not a IT statistician. When you want to create smoke and mirrors, obfuscate with astronomical numbers.

The statement in the preamble of the bill continues "...experts estimate that cyber attacks can produce $8,000,000,000 in annual loses to the national economy..." This is the argument of government. However, it does not dovetail with the four recorded incidents of governments either triggering a nationwide kill switch and terminating, for a brief to a prolonged partial, or complete, termination of Internet access or service to their citizens. In no instance to date has any government in the world ordered all of that nation's ISPs to terminate broadband and/or dial-up Internet service because they feared terrorists were about to launch a virus attack to wipe out their Internet infrastructure. In every instance where any government in the world has triggered their Internet kill switch (which every government in the world possesses), whether affecting only their broadband users, or both broadband and dial-up users, and whether those shutdowns were complete or impacted only segments of the Internet market in that country, those shutdowns or denials of access to the Information Superhighway targeted the law-abiding population at large whom those governments felt they had cause to fear.

Copyright © 2011 •Jon Christian Ryter.

All rights reserved.