News

Behind the Headlines

Two-Cents Worth

Video of the Week

News Blurbs

Articles

Testimony

Bible Questions

Internet Articles (2015)

Internet Articles (2014)

Internet

Articles (2013)

Internet Articles (2012)

Internet Articles (2011)

Internet Articles (2010)

Internet Articles

(2009)

Internet Articles (2008)

Internet Articles (2007)

Internet Articles (2006)

Internet Articles (2005)

Internet Articles (2004)

Internet Articles (2003)

Internet Articles (2002)

Internet Articles (2001)

exas

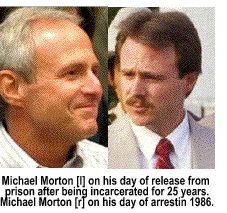

prosecutors agreed on Tuesday, Oct. 4, 2011 in the 26th Judicial Court

of Williamson County, Texas to release from prison an Austin man serving

a life sentence for the Aug. 13, 1986 beating death of his wife after

DNA evidence (not available at the time of the crime) found that another

man—a suspected serial killer—was responsible for the death

of Christine Morton. Michael Morton was arrested and charged

with his wife's death because, prosecutors said, Morton became

enraged and bludgeoned her to death because she wouldn't have sex with

him following a dinner to celebrate his 32nd birthday.

exas

prosecutors agreed on Tuesday, Oct. 4, 2011 in the 26th Judicial Court

of Williamson County, Texas to release from prison an Austin man serving

a life sentence for the Aug. 13, 1986 beating death of his wife after

DNA evidence (not available at the time of the crime) found that another

man—a suspected serial killer—was responsible for the death

of Christine Morton. Michael Morton was arrested and charged

with his wife's death because, prosecutors said, Morton became

enraged and bludgeoned her to death because she wouldn't have sex with

him following a dinner to celebrate his 32nd birthday.  Morton

was convicted entirely on circumstantial evidence, fanned into pseudo-reality

by then Williamson County District Attorney Kenneth Anderson, now

a Williamson County District Court Judge.

Morton

was convicted entirely on circumstantial evidence, fanned into pseudo-reality

by then Williamson County District Attorney Kenneth Anderson, now

a Williamson County District Court Judge.

Mistakes happen. Scores of innocent people are arrested, prosecuted and convicted of crimes they did not commit—usually as the result of overzealous prosecution or police fabricating evidence because "they are convinced their perp is guilty," and they want to make sure he doesn't escape justice. New York-based Innocence Project's co-Director Barry Scheck noted that, thus far, there have been 43 DNA conviction reversals in the State of Texas. That means at least 43 people were convicted of crimes they did not commit—in one State. How many were wrongly convicted where there was no DNA evidence to exonerate them? How many of those who were tried and sentenced for capital offenses were not "exonerated" until after they were executed for crimes they did not commit? How many mistakes were not mistake? Sometimes the mistake was not a evidentiary miscalculation or a persecutory judgment misstep. Sometimes it's a political opportunity by an opportunistic prosecutor trying to fast track his career with a few high profile convictions. It appears that may have been the case with Anderson's prosecution and conviction of Michael Morton.

The first bombshell came

when KXON-TV in Texas reported in September that DNA evidence recovered

on a bloodstained bandana found at a construction site 100 yards or so

from the Morton home contained Christine Morton's DNA—mixed

with that of a known violent sex offender from California. That DNA of

the same sex offender was found at a 1988 crime scene in Austin, Texas.

Killed

then was Debra Jan Baker, also beaten to death in her bed, on Jan.

12, 1988. An intruder broke into her Dwyce Drive home and raped her. Some

electronic items were taken.

Killed

then was Debra Jan Baker, also beaten to death in her bed, on Jan.

12, 1988. An intruder broke into her Dwyce Drive home and raped her. Some

electronic items were taken.

A Travis County judge, holding a recent hearing on that murder, heard evidence that would prove to be a bombshell in Judge Sid Harle's Bexar County courtroom on Sept. 26, 2011. Harle told an Innocence Project defense team and Williamson County prosecuting attorney John Bradley that he had sealed transcripts of "...a hearing taking place on a current criminal investigation in Travis County" that would have consequences in a 25-year old Williamson County murder.

Judge Harle told the lawyers representing Morton, and the DA's office which successfully convicted Morton in 1986, to "keep the information..." he had just given them "...confidential." After reading the transcript, John Raley, Morton's Innocence Project attorney, told Judge Harle that "...in light of this new information we should be prepared to agree to release Michael Morton immediately. Right now! And, if so, we want to discuss the immediate release of Michael Morton, and we would request the State cooperate with us..."

Neither Raley nor Bradley would confirm that Harle had established a connection between the Morton and Baker killings. But Caitlin Baker, the daughter of Debra Jan Baker told reporters that a detective from the Austin Police Department Cold Case Unit told her on Oct. 4 that authorities were investigating a connection between the two crimes. Debra Jan Baker lived 12 miles from the Morton home. On Jan. 13, 1988, Austin police singularly focused on one key suspect—Baker's estranged husband, Phillip Baker. Of course, the husband, like the proverbial butler, is always the best suspect. Just as Michael Morton was in 1986. Fortunately Baker, who worked at the county lockup, had an ironclad alibi. He was working.

However, District Attorney John Bradley, a Rick Perry protégé, did not agree to the immediate release of Morton. He wanted the DNA retested and verified by DPS. When the tests, for the second time, confirmed that Morton was not the killer, Bradley told the press that the new developments, which he said were "...a lightning bolt type of discovery, " warranted a reversal of Morton's murder conviction. "It is my job as District Attorney," he said, "to make sure that justice is done."

When the original investigation into the death of Christine Morton was taking place, then Williamson District Attorney Ken Anderson appears to have made a conscious-decision to suppress evidence that, even if it did not fully and completely exonerate Morton, would likely have precluded the police from arresting him, and Anderson from prosecuting him. First was the bloody bandana. Had it been tested, it might have saved Debra Jan Baker's life since the man who killed Christine Morton killed her. (The first DNA exoneration in the United States occurred in 1989. Courts in England were using DNA to support the arrest and prosecution of suspects in the early 1980s so, clearly the technology existed and was being used to exclude suspects.)

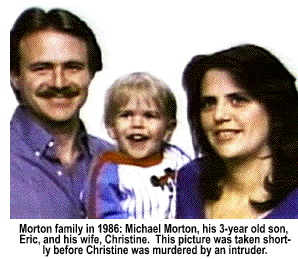

Second

was the telephone call from Michael Morton's mother-in-law to a

Williamson County sheriff's deputy soon after her daughter's murder. Rita

Kirkpatrick explained, in great detail, that Morton's 3-year

old son, Eric, watched the murder of his mother, and told his grandmother

that the monster with red gloves who killed his mother was not

his father. The State chose to ignore the statement because, in the view

of Anderson, an eye witness who was 3-years old is not a reliable

witness. (It's even money if Eric Morton saw his father bludgeon

his mother to death, he would have been the State's star witness.) In

Austin, it appears that Caitlin Baker, a toddler at the time, also

watched the same man kill her mother on Jan. 12, 1988. (In Montana on

Oct. 5, 2011, another 3-year old witnessed a murder. Sheldon Bernard

Chase, 22, killed his grandmother, Gloria Cummins, Levon

Driftwood (a cousin) and Reuben Jefferson, Driftwood's

boyfriend in their remote rural home on Montana's Crow Indian Reservation.

Will he testify at the trial? You bet. He's the only eye witness. Three

year olds are good witnesses—when they are witnesses for the prosecution.

When they are witnesses for the defense they are, of course, unreliable.

Second

was the telephone call from Michael Morton's mother-in-law to a

Williamson County sheriff's deputy soon after her daughter's murder. Rita

Kirkpatrick explained, in great detail, that Morton's 3-year

old son, Eric, watched the murder of his mother, and told his grandmother

that the monster with red gloves who killed his mother was not

his father. The State chose to ignore the statement because, in the view

of Anderson, an eye witness who was 3-years old is not a reliable

witness. (It's even money if Eric Morton saw his father bludgeon

his mother to death, he would have been the State's star witness.) In

Austin, it appears that Caitlin Baker, a toddler at the time, also

watched the same man kill her mother on Jan. 12, 1988. (In Montana on

Oct. 5, 2011, another 3-year old witnessed a murder. Sheldon Bernard

Chase, 22, killed his grandmother, Gloria Cummins, Levon

Driftwood (a cousin) and Reuben Jefferson, Driftwood's

boyfriend in their remote rural home on Montana's Crow Indian Reservation.

Will he testify at the trial? You bet. He's the only eye witness. Three

year olds are good witnesses—when they are witnesses for the prosecution.

When they are witnesses for the defense they are, of course, unreliable.

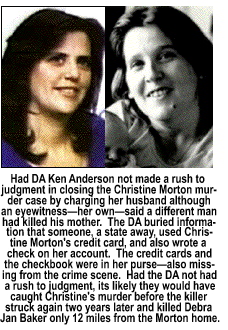

Also withheld from the defense attorneys in the original Morton trial was the fact that within two days of the murder someone had used Christine Morton's credit cards in an adjacent State. And, at about the same time, someone cashed a check drawn on her checking account. The killer, the prosecution forgot to tell the defense, also stole Morton's purse—and used her credit cards and checks—after Michael Morton was in custody. John Raley, the Innocence Project lawyer who won Morton's release from prison told ABC News "Those materials should have been turned over at the time of the trial. Then an innocent man would not have been convicted and spent 25 years of his life in prison."

How does the State give back

to Michael Morton the 25 years of his life it took? Granted, the

State will likely compensate him with money. But, how does the State give

back to him the life he missed? His son Eric was 3 years old when

Morton was led away from his home in handcuffs. Eric Morton

is now 28. There is no amount of money that can compensate either Michael

Morton or Eric Morton for their loss of each other's companionship

for a quarter-of-a-century. Eric Morton had to grow up without

either a mother or a father. And, Michael Morton suffered 25 years

without either his wife or son.  Both

of the Morton males became the victims of wrongful prosecution

by an overly aggressive prosecutor who appears to have been more concerned

about winning a conviction than he was about putting the right person

behind bars. If asked, I'm sure Judge Anderson would blame the

cops, reminding us that the police investigate and the DA prosecutes.

But the fact is, once a DA decides to prosecute, he leads the police investigation

to solidify the case he intends to present to a jury.

Both

of the Morton males became the victims of wrongful prosecution

by an overly aggressive prosecutor who appears to have been more concerned

about winning a conviction than he was about putting the right person

behind bars. If asked, I'm sure Judge Anderson would blame the

cops, reminding us that the police investigate and the DA prosecutes.

But the fact is, once a DA decides to prosecute, he leads the police investigation

to solidify the case he intends to present to a jury.

Had Anderson properly done the job he was hired to do by the citizens of Williamson County, there's a good chance that Debra Jan Baker might still be alive today because she probably would not have become the victim of Christine Morton's killer a year after Anderson won the conviction of the wrong man—someone Anderson had to know, based on the evidence he suppressed, was innocent of the crime a jury of his peers said he committed. Which meant if the police in Austin had done due diligence, there is a possibility the killer who left his DNA on the bandana a 100 yards from the Morton home would have been caught before any other victims died at his hand.

It is not enough, in this writer's view, that the State of Texas monetarily compensate Morton. They also need to take from Judge Anderson the "spoils of his victory"—his seat on the bench. Even that's not enough. Anderson should be made to sit in a cell in a State penitentiary for the next 25 years for two reasons. First, to see how an innocent man (even though he's not, by any stretch of the imagination, innocent) feels to be incarcerated; and second—and more important—to serve as a warning to overly aggressive prosecutors everywhere that when you conceal evidence that may exonerate the accused, you will face incarceration for the theft of that person's liberty. Every State in the Union needs to enact legislation that criminalizes knowingly suppressing evidence that points to the innocence of those accused of a crime. English law mandates that all evidence, even that which tarnishes the State's case, must be placed before the jury. It is the exclusive decision of jurists to determine what weight is attributed to each piece of evidence. When a prosecutor, or a judge, precludes evidence because it is inflammatory to the State's case, or to the Defense's case, you are depriving both the People and the accused, of a fair and completely impartial trial.

In a brief media interview after he was released from custody, Morton said: " I know there are a lot of things you want to ask me. I will say this: Colors seem real bright to me now; and the women are real good looking." Then, soberly, reflecting on what might easily have happened to him in 1987, he said: "Thank God this wasn't a capital case. They only had life...which gave the Innocence Project time to do this." Morton knows if he had been charged, and convicted of first degree murder—and sentenced to die—he would have been dead long before his innocence was proven. Today, the clock is ticking on what could easily be 2% to 5% of those sitting on death row who should not be there. Because in every State, there are zealously ambitious prosecutors who view the legal system as a political chess game where the winners become judges and governors and, thus, why winning is far more important than justice.

Under the Due Process clause

of the Constitution, the rules of evidence in the canon of law mandates

that the prosecution cannot legally suppress evidence in a criminal case

if that evidence establishes the innocence or raises doubt of the guilt

of the accused (unless that evidence is collected in some unconstitutional

manner). The information in the possession of then Williamson County,

Texas District Attorney Ken Anderson came to him in a lawful manner

and would have, at the very least, cast doubt on the guilt of Michael

Morton. It is likely that a jury would have declined to convict had

they heard the evidence Anderson's office suppressed.  In

fact, with that information, charges against Morton would likely

have been dropped long before he went to trial, and Morton would,

or at least should, have been released from custody.

In

fact, with that information, charges against Morton would likely

have been dropped long before he went to trial, and Morton would,

or at least should, have been released from custody.

The Innocence Project petitioned the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals to test the bandana. In April, the court granted their request. To get the court's approval, the Innocence Project had to get the other suppressed evidence into the court's hands over the objection of Bradley. Namely, a green van that was seen in the Morton neighborhood in the early morning hours of October 4, 1986. Neighbors reported seeing a man get out of the van and walk into a wooded area nearby.

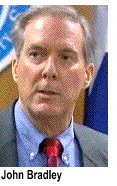

But the saga of the malady of Michael Morton doesn't stop here. Enter John Bradley, the current Williamson County District Attorney. What is interesting is that when Raley and the Innocence Project filed for the hearing that ultimately won Morton's release, they asked the court to recuse Bradley, the current DA and former Chairman of the Texas Forensics Science Commission.

Scheck and Raley said that while Bradley was the head of the Texas Forensic Science Commission he chose not to release what he knew would prove Morton did not murder his wife. In an interview with the Texas Tribune, Scheck noted that "...[i]t's clear from the new DNA testing and other suppressed, exculpatory documents that law enforcement never followed up on numerous leads pointing to a third-party intruder, which might have solved the crime. But even more troubling, District Attorney Bradley knew about this evidence, yet kept the documents hidden in the State's file while he fought tooth and nail to bar DNA testing [of the bandana]."

Bradley was appointed

to head the Texas Forensic Science Commission by Gov. Rick Perry

in 2001. Bradley was critical of efforts to examine questions raised

about the arson "science" used to convict Cameron Todd Willingham.

The fire Willingham was accused of deliberately starting in 1991

killed his three daughters. Willingham was executed in 2004.  The

investigation into the methodology used by the State Fire Marshal and

Texas Forensic Science Commission to rationalize arson was initiated by

the Innocence Project two years after Willingham's execution

sparked a 2006 report authored by John Lentini, a fire scientist

who has conducted over 2,000 fire scene inspections. Lentini reviewed

the evidence which led to Willingham's conviction. In his report,

he concluded that "...each and every one of the indicators [the

fire marshal's investigators] relied on have since been scientifically

proven to be invalid." In layman's language: there simply

was no arson. The fire had an accidental origin. No crime had been committed.

The

investigation into the methodology used by the State Fire Marshal and

Texas Forensic Science Commission to rationalize arson was initiated by

the Innocence Project two years after Willingham's execution

sparked a 2006 report authored by John Lentini, a fire scientist

who has conducted over 2,000 fire scene inspections. Lentini reviewed

the evidence which led to Willingham's conviction. In his report,

he concluded that "...each and every one of the indicators [the

fire marshal's investigators] relied on have since been scientifically

proven to be invalid." In layman's language: there simply

was no arson. The fire had an accidental origin. No crime had been committed.

In 2010, Fire Marshal Paul Maldonado rejected multiple fire science expert reports that concurred with Lentini's conclusions. Every report written by every fire expert agreed with Lentini's view. There was no arson. Again—it was not that someone else did it. The finding was that absolutely no crime had been committed by Willingham or anyone else. It was just a tragic house fire. Cameron Todd Willingham was convicted and executed for a crime that literally did not happen. And, once again, it was Gov. Rick Perry's cleanup person, John Bradley, trying to tidy up the embarrassing loose ends by doing his best to suppress an investigation designed to exonerate one more convicted, and executed, "killer." Executing an innocent man accused of committing a crime that did not happen does not look well on the resume of a governor seeking the Republican nomination for the presidency of the United States.

Copyright © 2011 •Jon Christian Ryter.

All rights reserved.