News

Behind the Headlines

Two-Cents Worth

Video of the Week

News Blurbs

Articles

Testimony

Bible Questions

Internet

Articles (2012)

Internet Articles (2011)

Internet Articles (2010)

Internet Articles

(2009)

Internet Articles (2008)

Internet Articles (2007)

Internet Articles (2006)

Internet Articles (2005)

Internet Articles (2004)

Internet Articles (2003)

Internet Articles (2002)

Internet Articles (2001)

US

District Court Judge exceeds her constitutional

authority by ruling that NSA can't eavesdrop on foreign

organizations or agents in overseas calls

Court-shopping for an ultraliberal federal judge that would be sympathetic to the plight of the American Civil Liberties Union was easy. The ACLU picked Jimmy Carter-appointee Anna Diggs-Taylor, US District Court Judge for the Eastern District of Michigan in Detroit. The ACLU knew Taylor as a kindred spirit for years. In 1984 when the ACLU wanted to ban the Nativity scene on municipal property in Birmingham, Alabama, they tossed Dearborn, Michigan into the lawsuit and went to court in Detroit. Taylor accommodated them, banning the Nativity not only in Dearborn where she had jurisdiction, but in Birmingham where she does not. Anna Diggs Taylor has been a good friend of the far left since her appointment to the federal judiciary in 1979.

Filing on behalf of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, Greenpeace and the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers was the ACLU. The fact that this was a lawsuit initially instigated by CAIR was camouflaged by adding other plaintiffs—including one academic and four internet journalists. The claims of injury were simply smoke and mirrors. The ACLU and the plaintiffs used half truths as whole truths. The journalists and the academic who claimed to be the injured parties were: James Bamford, a liberal author who writes exposes on the NSA and the American intelligence community; Larry Diamond of the centrist Hoover Institute. Diamond publishes the Journal of Democracy; Christopher Hitchens, a liberal web blogger; Tara McKelvey, senior editor of the website publication, American Prospect; and finally, a genuine academic—Dr. Barnett Rubin, Director of the Center for International Cooperation at New York University, and a policy wonk for the Council on Foreign Relations.

Anna

Katherine Johnston Diggs Taylor was educated at the prestigious Barnard

College at Columbia University, earning a degree in economics in 1957.

Three years later she graduated with a degree in law from Yale—only

one of 5 women in her graduating class, and the only African American.

She served as an assistant US Attorney in Detroit from 1966 to 1970 when

she went into private practice, specializing in civil rights law. In 1976

Taylor joined the presidential campaign of Jimmy Carter.

Carter rewarded her in May, 1979 with a lifetime berth on the US

District Court bench in Detroit. Taylor had no judicial experience

but the Democratically-controlled Senate confirmed her appointment in

October, 1979 anyway. If a GOP president had nominated a candidate for

the federal bench as conservative as Diggs-Taylor was liberal,

the liberals on the Senate Judiciary Committee would have spiked

the nomination, arguing that without judicial experience as a yardstick

to measure performance, they could not properly evaluate the worthiness

of the nominee as a candidate for the federal bench.

Anna

Katherine Johnston Diggs Taylor was educated at the prestigious Barnard

College at Columbia University, earning a degree in economics in 1957.

Three years later she graduated with a degree in law from Yale—only

one of 5 women in her graduating class, and the only African American.

She served as an assistant US Attorney in Detroit from 1966 to 1970 when

she went into private practice, specializing in civil rights law. In 1976

Taylor joined the presidential campaign of Jimmy Carter.

Carter rewarded her in May, 1979 with a lifetime berth on the US

District Court bench in Detroit. Taylor had no judicial experience

but the Democratically-controlled Senate confirmed her appointment in

October, 1979 anyway. If a GOP president had nominated a candidate for

the federal bench as conservative as Diggs-Taylor was liberal,

the liberals on the Senate Judiciary Committee would have spiked

the nomination, arguing that without judicial experience as a yardstick

to measure performance, they could not properly evaluate the worthiness

of the nominee as a candidate for the federal bench.

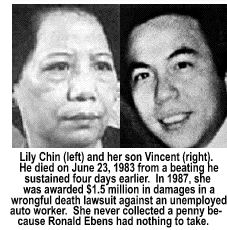

In addition

to the Nativity scene verdict in 1984, Taylor also presided over

the racial discrimination trial of Ronald Ebens that year. The

6th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned her verdict in that case and set

Ebens free. Ebens and his stepson, Michael Nitz killed

Vincent Chin on the night of July 19, 1982 after an incident at

the Fancy Pants Lounge in Highland Park, Michigan that ultimately

resulted in the beating death of the 27-year old Chinese-American engineer

who was celebrating his forthcoming marriage with a bachelor party at

the bar.  It's

unclear what precipitated the fight, or who threw the first punch. It

is likely the first blow was struck by Chin who was offended when

Ebens—an unemployed auto worker blamed the Japanese for stealing

the American auto market (thinking Chin was Japanese). The club's

bouncers threw all of the combatants out of the bar. Chin and his

friends left. Ebens and Nitz, who had been soundly thrashed

at the bar, found Chin at a local McDonald's a short time later.

Ebens had a Louisville Slugger. He hit Chin with the baseball

bat at least four times. Chin died from his injuries on June 23.

It's

unclear what precipitated the fight, or who threw the first punch. It

is likely the first blow was struck by Chin who was offended when

Ebens—an unemployed auto worker blamed the Japanese for stealing

the American auto market (thinking Chin was Japanese). The club's

bouncers threw all of the combatants out of the bar. Chin and his

friends left. Ebens and Nitz, who had been soundly thrashed

at the bar, found Chin at a local McDonald's a short time later.

Ebens had a Louisville Slugger. He hit Chin with the baseball

bat at least four times. Chin died from his injuries on June 23.

Ebens entered into a plea agreement with the State in 1983. He pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was placed on probation for three years. Chinese-American activists across the country were outraged and painted the killing as a hate crime, arguing that the State of Michigan trivialized the lives of Asian minorities. Responding to growing pressure nationwide, the Reagan Administration filed federal civil rights violations charges against Ebens. The trial was assigned to civil rights activist Judge Anna Diggs Taylor. She refused to allow the defense to argue that the Chinese-American "witnesses" were inappropriately coached to maximize the negative impact of their testimony. Knowing the testimony was tainted, Taylor still sentenced Ebens to 25 years—and fined him $20,000.

Ebens' lawyers immediately appealed Taylor's decision. The 6th Circuit Court granted the appeal. In 1986 the court ruled that the federal prosecutors had inappropriate coached witnesses and overturned Ebens' conviction. The federal government moved the retrial to Cincinnati, but this time, the evidence of witness tampering was admitted when others who witnessed the fight at the Fancy Pants Lounge were allowed to testify. Ebens was convicted the first time because witnesses coached by prosecutors claimed Ebens had made racial remarks, lending credence to the racial discrimination allegations—needed to convict Ebens of violating Chin's civil rights. This time, he was acquitted because no racial epitaphs were uttered by either Ebens or his stepson..

Taylor proudly wears her biases openly like a badge of honor for the world to see. Hardcore civil rights activists like Taylor should never be appointed to the federal judiciary. When the 6th Circuit overturned her verdict in the Ebens case, the federal magistrate said the "...entire experience was wrenching from start to finish." Not the trial—having her verdict overturned and having the defendant acquitted on the retrial. The ACLU judge-shopped Taylor by making the ACLU-Michigan a key component in the filing. The headquarters of the key defendant, CAIR—and both corporate co-defendants)—is Washington, DC. The plaintiff, the NSA, is headquartered in Washington, DC.

When she ruled in favor of the ACLU—with no evidence presented by any defendant that they had in any way, been damaged by the NSA surveillance program—Taylor awarded a major—albeit temporary (I hope)— victory to the Mideast Wahabbists who will benefit if her ruling is allowed to stand.

In Taylor's court, the ACLU did not even attempt to prove their clients were damaged—they simply argued that their clients might find it more difficult "...to do their jobs" in fear that the overseas telephone calls they make to "some contacts" might be monitored. Clearly, if Americans are talking to al Qaeda—or those connected to al Qaeda—then the National Security Agency should be listening. What in the world makes any American believe that conversations with those who want to destroy this nation should be construed to be privacy protected? There is no inherent right to privacy anywhere in the Constitution of the United States even though US Supreme Court Associate Justice Harry Blackmun tried to create one when he wrote the majority decision in Roe v Wade by claiming that a woman's right to privacy was so inviolable that she had an inherent right to evict the baby in her womb for intruding in it.

In

1994 when the Clinton Administration used warrantless surveillance

under the 1976 FISA Wiretap Act to eavesdrop on al Qaeda

cells operating in Afghanistan, the Mideast and in the European Union,

Deputy Attorney General Jamie Gorelick (one of the most vehement

anti-Bush 9-11 Commission members) argued to Congress that "...case

law supports that the president has inherent authority to conduct warrantless

searches for foreign intelligence purposes, and that the president may,

as has been done, delegate this authority to the attorney general."

When Clinton exercised this newfound "power," the

ACLU didn't file a lawsuit, nor was there any cries of outrage from civil

libertarians—or from the liberal Democrats who are now screaming

from the rooftops that President George W. Bush is violating the

Constitution by assuming authority he does not possess. The reason? Clinton's

use of the FISA apparatus was an exercise of inert motion (an oxymoron).

Even the terrorists knew that. Bill Clinton was a man that no one

feared—except, perhaps, the husbands of his paramours.

In

1994 when the Clinton Administration used warrantless surveillance

under the 1976 FISA Wiretap Act to eavesdrop on al Qaeda

cells operating in Afghanistan, the Mideast and in the European Union,

Deputy Attorney General Jamie Gorelick (one of the most vehement

anti-Bush 9-11 Commission members) argued to Congress that "...case

law supports that the president has inherent authority to conduct warrantless

searches for foreign intelligence purposes, and that the president may,

as has been done, delegate this authority to the attorney general."

When Clinton exercised this newfound "power," the

ACLU didn't file a lawsuit, nor was there any cries of outrage from civil

libertarians—or from the liberal Democrats who are now screaming

from the rooftops that President George W. Bush is violating the

Constitution by assuming authority he does not possess. The reason? Clinton's

use of the FISA apparatus was an exercise of inert motion (an oxymoron).

Even the terrorists knew that. Bill Clinton was a man that no one

feared—except, perhaps, the husbands of his paramours.

Constitutionally, no infererior court federal judge in this land can theoretically overrule the President of the United States. To allow an appointed federal judge to vacate a decision of the elected president is to suggest that a federal judge has more authority than the President of the United States—or that the judiciary can overrule the Executive. The Constitution of the United States very clearly established a system of governance in which the legislative, judicial and executive branches of government are separate, and that none have authority over the others. However, fail-safes were designed into the Constitution to make sure the Chief Executive did not usurp power not granted him by the Constitution or by Congress. Keep in mind that Congress cannot confer powers on the President that it, itself, does not possess.

.jpg) To

prevent the Chief Executive of the nation from assuming dictatorial powers

(as Federalist President John Adams attempted to when he criminalized

political opposition with the Sedition Act of 1798), the Constitution

delegated to the Supreme Court the authority to weigh the actions of the

Chief Executive against the Constitution to make certain the President

of the United States did not exceed the authority granted him. Additionally,

the Constitution did not give the federal court system the right of judicial

review. The high court unconstitutionally usurped that authority in 1803

in Marbury v Madison—just as the federal court system now

regularly and unconstitutionally rules on issues outside its authority.

When John Adams prosecuted 14 outspoken colonists—most of

them newspaper editors and publishers, including Matthew Lyons

a anti-Federalist member of the House of Representatives from Vermont—under

the Sedition Act for speaking out against him, the States rebelled

against the Federalists. The Virginia and Kentucky Resolves

nullified the Sedition Act of 1798. They also a repudiated the

Federalists themselves. No Federalist ever again won a presidential election.

Within 2 decades, the Federalist Party no longer existed.)

To

prevent the Chief Executive of the nation from assuming dictatorial powers

(as Federalist President John Adams attempted to when he criminalized

political opposition with the Sedition Act of 1798), the Constitution

delegated to the Supreme Court the authority to weigh the actions of the

Chief Executive against the Constitution to make certain the President

of the United States did not exceed the authority granted him. Additionally,

the Constitution did not give the federal court system the right of judicial

review. The high court unconstitutionally usurped that authority in 1803

in Marbury v Madison—just as the federal court system now

regularly and unconstitutionally rules on issues outside its authority.

When John Adams prosecuted 14 outspoken colonists—most of

them newspaper editors and publishers, including Matthew Lyons

a anti-Federalist member of the House of Representatives from Vermont—under

the Sedition Act for speaking out against him, the States rebelled

against the Federalists. The Virginia and Kentucky Resolves

nullified the Sedition Act of 1798. They also a repudiated the

Federalists themselves. No Federalist ever again won a presidential election.

Within 2 decades, the Federalist Party no longer existed.)

Two things should come to mind over the high court's dealing with the Sedition Act of 1798. First, just a dozen years after the ratification of the Constitution, the Federalist Supreme Court allowed party politics to blind them to their role as protectors of the of the Bill of Rights. The primary role of the high court has always been that of caretaker of the Constitution. They should have ruled the Sedition Act of 1798 unconstitutional. Interestingly, it should be noted that in actions initiated by the Executive Branch, the US Supreme Court was the court of record for those cases. This is why the US Supreme Court heard the sedition cases resulting from the Sedition Act of 1798.

Second, not only did they not do that, but the original five justices found the 14 defendants charged by the Adams Justice Department guilty of the seditious act of criticizing the president. The Supreme Court sent them to jail for six months and fined them $1,000. Because most of those sentenced did not have $1,000, the federal government seized their property—just because they criticized John Adams. These men had no First Amendment right to free speech, nor did they have a Fourth Amendment right to avoid having their property seized. They did, however, retain the protection of the Sixth Amendment. They got a speedy trial. But they lost their Seventh Amendment rights because they were denied a trial by jury.

Shocked? You shouldn't be. With respect to the First Amendment, the Constitution says "Congress shall make no laws respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.." There is no ambiguity here for lawyers to trip over. The ambiguity comes from the attempt of the courts to supplant the First Amendment with Article 18 § 3 of the International Covenant on Civil & Political Rights. The increasingly social activist federal judiciary, which has largely been internationalized, has no problem supplanting an inherent right with a conditional one.

As you examine the quality of the liberty found in the Constitution of the United States and the "freedom" granted by the International Covenant on Civil & Political Rights you can see the difference between natural rights and conditional rights. Under the Constitution, we see that "...Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof..." The Founding Fathers placed all of the restrictions on the government. Somewhere along the road to the toll road to Utopia—thanks to the ACLU and activist federal judges like Taylor—the meaning of the First Amendment has become so fuzzy that, now, all of the restrictions are placed on the citizen who no longer possesses an inherent right to practice the free exercise of religion. The federal courts—backed up by the US Supreme Court—now interpret religious freedom in the manner of the privileges described in Article 13 of the Covenant on Human Rights: "Freedom to manifest one's religion or beliefs may be subject only to such limitations that are prescribed by law..." All of the prohibitions are placed on the people. None are placed on the government. What's wrong here? Activist judges like Anna Diggs Taylor.

The ACLU sought legal cover not so much from the fact that it appeared that the Bush-43 Administration had exceeded its legal authority by eavesdropping without a FISA judge-authorized warrants under Title III of the Wiretap Act (that is part of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act [FISA]), but rather, it wrapped itself in a constitutional issue on a mistaken belief that the NSA violated the free speech rights of the American people because, with the NSA eavesdropping on international calls, those people contacting clients or sources associated with terrorist organizations in Europe, Asia or Central or South America, would not feel comfortable speaking "freely" to them on the telephone or by email.

Although none of the plaintiff's in American Civil Liberties Union, et al v National Security Agency, et al offered any evidence to show they had been injured by not being able tospeak freely to their foreign contacts because of the NSA wiretaps, CAIR probably could probably have made a good case to support the contention that they had been hamstrung by the NSA. As she announced her decision, Taylor said: "There are no hereditary kings in America—and no powers not created by the Congress...The irreparable injury necessary to warrant injunctive relief is clear," she said, "as the firsst and fourth Amendment rights of plaintiffs are violated." In point of fact, they were not.

As the lawyers for the NSA pointed out, the claims of the defendants should have been dismissed because the plaintiffs did not establish a prima facie case. The claims of alleged injury by the plaintiffs were too tenuous, not at all concrete nor particularized. In the core of the plaintiff's filing, the ACLU contended that the government interfered with their ability to talk with sources, locate witnesses, engage in advocacy and communicate with people outside the United States. McKelvey, Diamond and Rubin argued that their jobs entail extensive research in the Mideast, Africa and Asia and, in that research, they must communicate with individuals abroad who are viewed by the US government as terrorist suspects or are associated with known or suspected terrorist organizations. If that is so, then each of them needs to understand that terrorists don't get a waiver because an American reporter wants to interview them off-the-record.

The ACLU claimed in their filing that the NSA's surveillance "...caused clients, witnesses and sources to discontinue their communications with plaintiffs out of fear that their communications will be intercepted. They also allege injury based on the increased financial burden they incur in having to travel substantial distances to meet personally with their clients and others relevant tot heir cases." Taylor noted in her decision that "...[t]he ability to communicate confidentially is an indispensable part of the attorney-client relationship."

Let's keep this in perspective, folks. When attorney's fly to visit clients in another country, they are "on the clock" the whole time. Not only does the client pay the plane fare, they also pay $200 to $500 an hour—or more—for all the time the attorney is away from home. It may cost the defendant a few bucks more, but it doesn't cost the attorney more. He profits from a premium rate while out of the country. As far as the writers are concerned, the "clients," (i.e., terrorist organizations) are clueless that Echelon is monitoring their calls only if they haven't been reading American periodicals for the past couple of decades. And, since they don't have an American constitutional right to privacy, suspected terrorists or terrorist organizations, or known or suspected terrorist States, should not have an expectation of privacy—nor should those who wish to communicate with them. Nor should any federal magistrate be allowed to construe that such people suffered "...irreparable injury" because the US government used FISA wiretapping protocols to eavesdrop on non-Americans in foreign countries. The expectation of privacy is a right American citizens talking with other US citizens should expect. In the event the government wishes to intrude on those conversations, they are required to secure a warrant from a judge. But extending the protection of the Constitution to foreigners who would use that protection to harm us is ridiculous. And, placing a shield up so that agendized Muslim groups like CAIR can communciate with their compatriots in the Mideast without fear of having their conversations monitored by national security or intelligence agencies is equally as stupid.

When the ACLU v NSA decision was handed down, White House spokesman Tony Snow said that the Bush Administration's program—implemented immediately following the 9-11 terrorist attacks—is "...firmly grounded in law and regularly reviewed [by the FISA court] to make sure steps are taken to protect civil liberties." Snow added that the Administration could not disagree more with Taylor's ruling. "Last week," he added, "America and the world received a stark reminder that terrorists are still plotting to attack our country and kill innocent people. United States intelligence officials have confirmed that the program has helped stop terrorist attacks and saved American lives. The program is carefully administered, and only targets international phone calls coming in or out of the United States where one of the parties on the call is a suspected al Qaeda or affiliated terrorist. The whole point is to detect and prevent terrorist attacks before they can be carried out. That's what the American people expect from their government, and it is the president's most solemn duty to ensure their protection."

ACLU Executive Director Anthony Romero told reporters that Taylor's decision was "...another nail in the coffin in the Bush Administration's...strategy in the war on terror." Liberal Vermont US Sen. Patrick Leahy—the ranking Democrat on the Senate Judiciary Committee said the Taylor opinion simply highlighted one more "...unfortunate example of how White House misdirection, arrogance and mismanagement [has] needlessly complicated our goal of protecting the American people." (I'm personally amazed that Leahy, like House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi who called Taylor's decision a "repudiation of the Bush Administration", had the gall to include himself with those who are trying to protect the American people.)

The decision that came from Judge Taylor's court was expected. That was, after all, why the ACLU judge-shopped her courtroom. She's a hard-left civil rights political activist whose decision was a sure-thing before the case was filed. Taylor has been a judge whose advocacy was more important than justice—at least since 1998. That year an affirmative action case involving the University of Michigan—where her husband, Martin Taylor, was a Regent was on the docket. As Chief Judge, Taylor tried to pull rank and take the case away from Judge Bernard Freedman who was assigned it in a blind draw. Taylor did not want the case in Freedman's court because the jurist was not an advocate of affirmative action. Attempting to wrest the case from him, she justified her heavyhandedness to friends by saying"...[w]e can't have somebody that's biased that way. We need somebody like me, biased my way, towards affirmative action. That's what's fair in my courtroom." Bias is good in Judge Anna DiggsTaylor's courtroom— providing its leftwing bias.

Taylor agreed not to hear the case only when Freedman—a Reagan appointee—went public and told the media what she had done. When she was forced to reassign the case, she tried to pass it to another affirmative action judge by consolidating it with a case dealing with the University of Michigan's undergraduate admission's project that was assigned to Judge Patrick Duggan. In the end, Freedman heard the case. But by a 5 to 4 vote, the 6th US Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the existing affirmative action program of the University of Michigan—which is what Taylor wanted. Because of the judicial improprieties in Taylor's court, the Wall Street Journal raised the question in its June 18, 2002 issue of whether or not Congress would launch an investigation of the federal court's handling of the case. They didn't. Biased judges on the federal courts didn't seem to bother Congress. After all, they made the mess. And besides, when their friends need to judge-shop, its nice if they know where to go to get the verdicts they want.

Well, once again, you have my two cents worth on this subject.

Copyright © 2009 Jon Christian Ryter.

All rights reserved.