News

Behind the Headlines

Two-Cents Worth

Video of the Week

News Blurbs

Articles

Testimony

Bible Questions

Internet Articles (2015)

Internet Articles (2014)

Internet

Articles (2013)

Internet Articles (2012)

Internet Articles (2011)

Internet Articles (2010)

Internet Articles

(2009)

Internet Articles (2008)

Internet Articles (2007)

Internet Articles (2006)

Internet Articles (2005)

Internet Articles (2004)

Internet Articles (2003)

Internet Articles (2002)

Internet Articles (2001)

hen

Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg delivered a speech

to the South African Constitutional Court on Feb. 7, 2006,

she spoke of the need for national courts to incorporate international

law—or as she put it, foreign decisional law—in the measures

being debated by those courts. Ginsburg, who indicated that

international law was acquiring a real position in the decision-making

process of the US Supreme Court in 2004, noted that the Republican-controlled

Congress would terminate all debate over whether or not the federal

judiciary could, or should, refer to foreign or international legal

materials when considering the cases before them. "For the

most part," Ginsburg told the audience of South

African judges, "they would respond to the question with

a resounding 'No!' Two identical resolutions," she continued,

"were reintroduced last year—one in the House of Representatives

and the other in the Senate.

hen

Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg delivered a speech

to the South African Constitutional Court on Feb. 7, 2006,

she spoke of the need for national courts to incorporate international

law—or as she put it, foreign decisional law—in the measures

being debated by those courts. Ginsburg, who indicated that

international law was acquiring a real position in the decision-making

process of the US Supreme Court in 2004, noted that the Republican-controlled

Congress would terminate all debate over whether or not the federal

judiciary could, or should, refer to foreign or international legal

materials when considering the cases before them. "For the

most part," Ginsburg told the audience of South

African judges, "they would respond to the question with

a resounding 'No!' Two identical resolutions," she continued,

"were reintroduced last year—one in the House of Representatives

and the other in the Senate.  [They]

declared that 'judicial interpretations regarding the meaning of

the Constitution of the United States should not be based on judgments,

laws or pronouncements of foreign institutions unless such [material]

informs an understanding of the original meaning of the Constitution.'

As of December, 2005, the House Resolution had attracted support

from 83 cosponsors. Two 2005-proposed Acts would do more than 'resolve,'"

she added. "They would positively prohibit federal courts,

when interpreting the Constitution, from referring to any constitution,

law, administrative rule, Executive Order, directive, policy, judicial

decision, or any other action of any foreign state or international

organization or agency—other than English constitutional or

common law up to the time of the adoption of the US Constitution."

[They]

declared that 'judicial interpretations regarding the meaning of

the Constitution of the United States should not be based on judgments,

laws or pronouncements of foreign institutions unless such [material]

informs an understanding of the original meaning of the Constitution.'

As of December, 2005, the House Resolution had attracted support

from 83 cosponsors. Two 2005-proposed Acts would do more than 'resolve,'"

she added. "They would positively prohibit federal courts,

when interpreting the Constitution, from referring to any constitution,

law, administrative rule, Executive Order, directive, policy, judicial

decision, or any other action of any foreign state or international

organization or agency—other than English constitutional or

common law up to the time of the adoption of the US Constitution."

Ginsburg

told her South African audience that while she doubted that the

proposed resolutions would ever pass through Congress and actually

be signed into law, she was disturbed about two things. First, it

troubled her that the legislation attracted as many cosponsors in

the House and Senate that it did since it was her opinion that the

resolutions were fueled by a fringe element on the far right and

not by mainstream-thinking legislators.  Second,

she was disquieted that Congress would willingly impose their will

on the federal judiciary by limiting the materials the courts could

refer to in contemplating their decisions. What

convinced her that the legislation was "fueled" by the

fringe element of the far right was a dialogue on a rightwing militant

blog suggested that both Ginsburg and now retired Associate

Justice Sandra Day O'Connor were being targeted by rightwing

extremists. The Supreme Court Marshall alerted O'Connor on

Feb. 28, 2005 of a web posting that threatened their lives because

of public statements that O'Connor and Ginsburg intended

to incorporate European court decisions, and decisions by the International

Criminal Court and the International Court of Justice

(the World Court), into their rulings.

Second,

she was disquieted that Congress would willingly impose their will

on the federal judiciary by limiting the materials the courts could

refer to in contemplating their decisions. What

convinced her that the legislation was "fueled" by the

fringe element of the far right was a dialogue on a rightwing militant

blog suggested that both Ginsburg and now retired Associate

Justice Sandra Day O'Connor were being targeted by rightwing

extremists. The Supreme Court Marshall alerted O'Connor on

Feb. 28, 2005 of a web posting that threatened their lives because

of public statements that O'Connor and Ginsburg intended

to incorporate European court decisions, and decisions by the International

Criminal Court and the International Court of Justice

(the World Court), into their rulings.

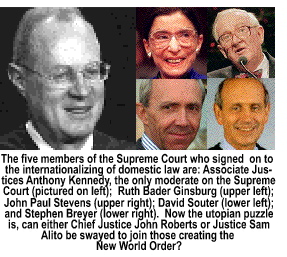

In point of fact, while Ginsburg and O'Connor may have been more transparent on their belief than Associate Justices John Paul Stevens, David Souter, and Stephen Breyer, all of them ascribe to the globalist views of the International Law institute and the International Judiciary Academy. The utopian view is that it is imperative to very subtly weave the tenets of international law into the domestic courts of the nations in order to strengthen the administration of justice.

On the web blog posting theoretically shown to Justice O'Connor by the Supreme Court Marshall, Ginsburg told the South Africans that a blogger said: "Okay, commandoes, here is your first patriotic assignment...an easy one. Supreme Court Justices Ginsburg and O'Connor have publicly stated that they use [foreign] laws and rulings to decide how to rule on American cases. This is a huge threat to our Republican and Constitutional freedom...If you are what you say you are, and not armchair patriots, then those two justices will not live another week." Not that I'm calling the jurist a liar but logic, on the face of it, suggests that story did not happen. Why? Because if rightwing bloggers had threatened the lives of the only two female members of the US Supreme Court—particularly two members who had signed on to the utopian agenda of melding international law into domestic law—the story would have headlined the news for days—all over the world. Arrrests would have been made and the trials of the extremists would have headlined the evening news for even more months.

In

reality, what the international judicial NGOs (non-governmental

organizations) are attempting is to domesticate international law.

This would allow transnational legal rulings to infiltrate American

jurisprudence through both civil and criminal codes and acquire

legal standing as lawful precedents in American courts—at every

level of the judicial hierarchy. This would serve to bind American

judges not only to laws—and the legal logic—enacted by

the European Union in the Hague, but those enacted by the governments

in Beijing, Moscow, Havana—and Tehran. Why would Ginsburg—and

Stevens, and Souter, and Breyer—willingly

pollute American law by incorporating foreign judgments, administrative

rules, or white papers by NGOs into the legal logic of their adjudication?

In

reality, what the international judicial NGOs (non-governmental

organizations) are attempting is to domesticate international law.

This would allow transnational legal rulings to infiltrate American

jurisprudence through both civil and criminal codes and acquire

legal standing as lawful precedents in American courts—at every

level of the judicial hierarchy. This would serve to bind American

judges not only to laws—and the legal logic—enacted by

the European Union in the Hague, but those enacted by the governments

in Beijing, Moscow, Havana—and Tehran. Why would Ginsburg—and

Stevens, and Souter, and Breyer—willingly

pollute American law by incorporating foreign judgments, administrative

rules, or white papers by NGOs into the legal logic of their adjudication?

Ginsburg summarized her views by telling the South Africans that utilizing international "natural" law in the United States is necessary because the US Constitution is "...a document frozen in time as of the date of its ratification," adding that she was "...not a partisan of that view. US jurists honor the Framers' intent to create a more perfect Union. I believe," she added, "if they read the Constitution as belonging to a global 21st century, not fixed forever by 18th century understandings of European and African liberals to unilaterally amend a Constitution written by benighted 18th century Americans as such Ben Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, George Washington and James Madison." In her final explanation, Ginsburg clearly reveals she is partisan of the view that the Constitution must evolve to survive.

And that, pretty much, has been the crux of the battle between conservative White Houses and the liberals on the US Senate Judiciary Committee since the Warren Court in 1954—denying a berth on the federal bench to any rule of law jurist and confirming only those judges who would apply the precepts of social justice to case law that would necessarily weaken, if not destroy, the Bill of Rights, as the Utopians within government and the wealthy barons of banking and industry prepared America for its admission into the global hierarchy of the New World Order.

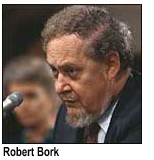

In his

1990 book, "The Tempting of America," former US

District Court Judge and foiled Reagan Supreme Court nominee

Robert H. Bork noted that: "[t]he

central problem for constitutional courts is the resolution of the

'Madisonian dilemma'... The

dilemma is that neither majorities or minorities can be trusted

to define the proper spheres of democratic authority and individual

liberty. To place that power in or the other would risk either tyranny

by the majority or tyranny by the minority. The Constitution deals

with the problem in three ways: by limiting the powers of the federal

government; by arranging that the President, the senators and the

representatives would be elected by different constituencies voting

at different times, and by providing a Bill of Rights. The last

is the only solution that directly addresses the specific liberties

minorities are to have." The Bill of Rights,

the instrument used to protect liberty became the problem of the

utopians who wanted to redefine that liberty based on the needs

of an evolving global—not national—society.

The

dilemma is that neither majorities or minorities can be trusted

to define the proper spheres of democratic authority and individual

liberty. To place that power in or the other would risk either tyranny

by the majority or tyranny by the minority. The Constitution deals

with the problem in three ways: by limiting the powers of the federal

government; by arranging that the President, the senators and the

representatives would be elected by different constituencies voting

at different times, and by providing a Bill of Rights. The last

is the only solution that directly addresses the specific liberties

minorities are to have." The Bill of Rights,

the instrument used to protect liberty became the problem of the

utopians who wanted to redefine that liberty based on the needs

of an evolving global—not national—society.

The liberals "problem" with the Bill of Rights is not that it s "frozen in time" as suggested by Ginsburg, and thus, needs to be "thawed" by the temperate mood of an evolving civilization at the gateway of Utopia in the 21st century. The Bill of Rights is completely neutral in its immunity and thus, it's ageless. It protects society by protecting all of the people from the conniving underhandedness of government as it protects the nation from the prejudices of the majority against the minority—and the racial, religious, ethnic and cultural prejudices of the minority against the majority. It is the most equal thing in our unequal world. The wisdom of the Founding Fathers exceeds the combined intellect of all of the Nobel laureates, junk yard lawyers and constitutional scholars combined.

The Bill of Rights was the structured authority that prevented Woodrow Wilson from legislatively abolishing national sovereignty to the utopian barons of industry and banking who desired a world government without trade borders or tariffs in 1920. It did its job again just prior to the outbreak of World War II when Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill met on battleships in Placenta Bay off the coast of Newfoundland on Aug. 109, 1941. The White House press corps called the agreement they signed the Atlantic Charter. In reality it was nothing more than the surreptitious reclothing of the failed European League of Nations in a neatly tailored red, white and blue, star-spangled Uncle Sam-camouflagued version of the same utopian organization that was actually created by the robber barons and bankers who wanted a borderless, tariff-free Europe in 1920. The remodeled—but virtually unchanged—version was called the United Nations. Roosevelt and the utopians had duped the American people. The world government-in-waiting had simply been made to look American.

The utopians who attempted to create world government at the end of World War I were quick to grasp the simple reality that the nationalistic fervor that fuels patriotism is rooted in faith—Christian faith. It became very clear to the one-worlders between the two world wars that, before American sovereignty could be breached and the United States re-shackled to the Old World Order the utopians, the Bill of Rights—which Ginsburg claimed was frozen in time—would have to be abolished and replaced with the UN Declaration of Human Rights.

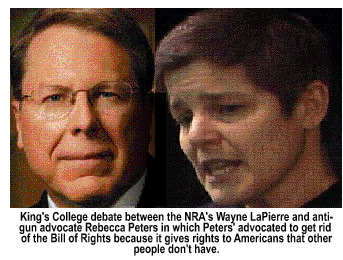

When

then Executive Vice President (now CEO) of the National

Rifle Association [NRA] Wayne LaPierre debated Rebecca

Peters, the head of the International Action Network of Small

Arms [IANSA] at Kings College in London on Oct. 12, 2004 on

the issue of gun control, she advocated abolishing the Bill of Rights

to eliminate the 2nd Amendment. In her own words, Peters

told the audience of largely anti-gun advocates she believed the

American Bill of Rights should be abolished and replaced with the

UN Declaration of Human Rights, adding

that she didn't believe Americans should have rights that no other

people in the world possess. Peters was much

more circumspect about the ageless character of the Bill of Rights

than Associate US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

who referred to the same Bill of Rights as an archaic relic that

was "frozen in time."

When

then Executive Vice President (now CEO) of the National

Rifle Association [NRA] Wayne LaPierre debated Rebecca

Peters, the head of the International Action Network of Small

Arms [IANSA] at Kings College in London on Oct. 12, 2004 on

the issue of gun control, she advocated abolishing the Bill of Rights

to eliminate the 2nd Amendment. In her own words, Peters

told the audience of largely anti-gun advocates she believed the

American Bill of Rights should be abolished and replaced with the

UN Declaration of Human Rights, adding

that she didn't believe Americans should have rights that no other

people in the world possess. Peters was much

more circumspect about the ageless character of the Bill of Rights

than Associate US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

who referred to the same Bill of Rights as an archaic relic that

was "frozen in time."

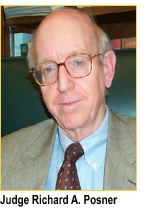

Seventh

US Circuit Court Chief Judge Richard A. Posner—one of

the most brilliant, and outspoken, conservative judges on the federal

bench—has made it clear in his writings that the opinions of

foreign judges are not authoritative and have no place in American

jurisprudence. They set no binding precedent that obligates a US

judge to use their arguments in shaping their decision.  Posner

admitted, however, that the thinking behind the legal opinions of

foreign judges may offer a storehouse of knowledge could be relevant

in the decision process of the judiciary. But the view of the Chief

Judge is that "...[t]o cite foreign law as authority is

to flirt with the discredited idea of a universal natural law, or

to suppose fantastically that the world's judges constitute a single,

elite community of wisdom and conscience."

Posner

admitted, however, that the thinking behind the legal opinions of

foreign judges may offer a storehouse of knowledge could be relevant

in the decision process of the judiciary. But the view of the Chief

Judge is that "...[t]o cite foreign law as authority is

to flirt with the discredited idea of a universal natural law, or

to suppose fantastically that the world's judges constitute a single,

elite community of wisdom and conscience."

It is likewise the view of Associate Justice Antonin Scalia that the high court has no authority to consider foreign law as a "guide" in rendering decisions in cases which do not deal with international issues or with international litigants. Ginsburg, of course, disagrees. "Judges in the United States," Ginsburg noted in her address to the Constitutional Court of South Africa, "are free to consult all manner of commentary—restatements, treaties, what law professors or even law students write copiously in law reviews. For example, if we can count those writings, why not the analysis of a question similar to the one we confront contained in an opinion of the Supreme Court of Canada, the Constitutional Court of South Africa, the German Constitutional Court, or the European Court of Human Rights?...The notion that it is improper to look beyond the borders of the United States in grappling with hard questions...is in line with the view of the US Constitution as a document essentially frozen in time as of the date of its ratification."

Ginsburg noted that's the reason that the Supreme Court is now casting comparative sideglances at the opinions of humankind. When the court was weighing Roper v Simmons in March, 2005, it looked at the propriety and utility of the whole spectrum of international law to gain a fresh assessment of the evolving standards of decency.

Roper v Simmons was heard on Oct. 13, 2004. In a 5-to-4, Mar. 1, 2005 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the 8th and 14th Amendments forbid the execution of offenders who were under the age of 18 when their crimes were committed. That's not true. The courts of Europe determined that society can't execute offenders under the age of 18. The 8th Amendment merely says the courts can't impose cruel or unusual punishment. The 14th Amendment applies the restrictions of the Bill of Rights to the States when, originally, they applied only to the federal government. While anti-death penalty advocates believe the death sentence is a cruel punishment because it takes the life of those it is imposed upon. However, the principle of an eye-for-an-eye is Biblical, and death is the only sentence that should be imposed upon those who, with malice, take the life of another.

Justice Kennedy wrote the majority opinion in Roper v Simmons. In writing the opinion, Kennedy noted that "...the opinion of the world community provides respected and significant confirmation of our own conclusions. It does not lessen our fidelity to the Constitution." Although Kennedy sits on a bench where everything he says—if he's part of the majority—is right (since he is writing law when he speaks), in this case he was wrong. Kennedy, Breyer, Ginsburg, Souter, and Stevens wrote the majority opinion in Roper. In Roper, Kennedy—who actually wrote the opinion—stated that the view of the world community provides "...respected and significant confirmation of our own conclusions. Kennedy said "The overwhelming weight of international opinion against the juvenile death penalty...does not lessen our fidelity to the Constitution...[or recognize] the express affirmation of certain fundamental rights by other nations and peoples." In Roper, the high court accepted amicus briefs from former President Jimmy Carter, who urged the high court to "...consider the opinion of the international community, which has rejected the death penalty for child offenders worldwide." In addition, amicus briefs were filed by South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and South Africa's former president, Willem de Klerk. Ginsburg, like her liberal peers on the high court, believe the Supreme Court will accept the opinions of humankind as a matter of comity because as the world gets smaller and our enemies closer, she is convinced that all nations will be forced to trust all other nations—and cooperate with them to make all nations safe by the same accord.

That accord is not being written by a judicial consensus based on the rule of law in the United States, but by the utopian rules of quixotic men whose views were shaped and supported by the chimeric foundations of wealthy industrialists and bankers who have been carefully tailoring world government—to be controlled by them—one layer at a time, since 1905. One of the tasks of the global nation builders has been to structure the plenary rules by which all men in all nations shall accord themselves or be judged by the International Court of Justice—the World Court—in the Hague. At the heart of the effort to create uniform laws throughout the world is an organization called the International Law Institute [ILI], created in 1955 at the Georgetown University Law Center. A sister center, the Insitut Auslandisches und Internationales Wirtschaftscrecht was founded in Frankfurt, Germany at the Johannes Goethe University. The purpose of the Institute was to create a uniform legal system between Europe and America in order to facilitate transnational business and trade and to create a single global economic community out of the world. Stemming from the ILI is the International Judicial Academy whose job it would be to train judges to use domesticated international law in formulating their judicial decisions.

The ILI's first Director, Professor Heinrich Kronstein, fled Germany in the 1930s when Hitler assumed power. In the 1970s, Professor Don Wallace, Jr., a Georgetown law professor assumed the reins of the ILI, expanding its focus to include professional training in the legal, economic and financial problems of developing countries. In the 1990s, the role of the Institute were expanded again to include the problems facing the new nations that were part of the Soviet Union as they transitioned from socialism to free market economies, and from totalitarianism to the rule of law. While the ILI is headquartered in Washington, DC, there are regional centers in Kampala, Uganda; Abuja, Nigeria; Cairo, Egypt; Santiago, Chile and Hong Kong, SAR. Within this decade, the ILI expects to have offices located in Moscow, Russia; Beijing, China; Pyongyang, North Korea; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and Tehran, Iran.

The ILI now advises governments—including China—and multilateral NGOs on societal problems, the revision of regulations, legislation drafting, contract law and criminal law standardization, the standardization of banking regulations, and hundreds of other transnational projects that have gone literally unnoticed for a half century by the common, working class people of the world whose governments were working behind their backs to dissolve sovereignty and create a stateless community of nations governed by the UN not in New York, but at the Hague.

At the heart of the ILI are training programs and seminars for participants from the public and private sectors. The topics range from international business, investment, governance and law. The ILI's mission is to raise the levels of professional competence and capacity in every nation and, by creating uniform standards of law, establishing a level playing field in the international arena. Centermost is the training of judges, lawyers, government officials, bankers, industrialists, business managers and other interested parties that, in the fast-moving global economy of the 21st century, those who are going to succeed—nations, corporations or individuals—must grasp the changing patterns of international commerce, banking, communications, and all facets of governance, adapt and master the skills needed to thrive in the global economy.

To begin preparing the world for the global community, the Inter-American Development Bank [IDB] (which is owned by 47-UN member nations) and the Washington College of Law hosted its first seminar on incorporating international law into domestic courts from Nov. 10-14, 1997. The seminar was attended by 45 judges, prosecutors and public defenders from 18 different Latin American countries. The aim of the project was to familiarize the attendees with the precepts of international law and inter-American human rights. The primary training goals of the IDB/WCL is judicial reform.

While the judicial courses are designed for judges at every judicial level, the project planners specifically target federal judges at the appellate level for several reasons. They affect judicial "policy" and the nature of law on a daily basis. Their decisions influence the rulings of judges at all lower levels. At that time—in 1997, a decision was made not to target Supreme Court justices since the high courts generally hear only a small number of cases per year. That philosophy has now changed, and beginning in 1999, all of the US Supreme Court Justices except Rehnquist, Scalia and Thomas attended at least one seminar on incorporating international law into domestic courts.

The project planners of Utopia initially targeted judges at the appellate level believing they have the strongest influence over the lower courts, and in the belief that the justices in the nation's highest court would be immune from tampering. However, in 2004 the US Supreme Court delivered decisions in four cases dealing with International law: Republic of Austria v Altmann; Rumsfeld v Padilla; Rasul v Bush; Hamdi v Rumsfeld; and Sosa v Alverez-Machain. The issues of international law that were specifically examined in those cases were: [1] the reach of the Alien Tort Claims Act, [2] the retroactively of the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, [3] the jurisdiction of US courts in the detention of foreign nationals, and [4] the rights of detainees to challenge their classification as enemy combatants. As the Rehnquist Court was obligated to deal with these international issues, some members of the high court began grappling with an even larger issue—at what point, and to what extent, should international law influence domestic law. That is the same issue being debated at the ILI. The answer—from the liberal perspective—is that, international law should affect every court, at every level, as quickly as possible.

That's why, in 2005, the International Judiciary Academy of Washington, DC, began holding educational seminars and lectures for 20 State-level trial and appellate judges. Not only will lower courts begin to incorporate international legal opinions in their decisions, the Utopians want to make sure there is an adequate pool of "qualified and approved" candidates for the federal bench—particularly, nominees for the appellate level courts.

Like the institutionalized deadwood that occupies the seats of both Houses of Congress because they've been in Washington, DC too long, federal judges are theoretically institutionalized from the moment they are confirmed to the bench because they have been given a lifetime berth and are answerable to no one. We can remove any politician—even the most powerful—in the voting booth, but we can't vote federal judges off the bench. However, we can impeach them. It's time to sent a message to the federal court system. Boot Ruth.

Copyright © 2009 Jon Christian Ryter.

All rights reserved.